- Global Rank: G1 Key to global and state ranks

- State Rank: SXB

- WBCI Priority: SGCN

- Breeding Range: 1) Wood Buffalo National Park, Northwest Territories, Canada; 2) Central Florida; 3) Central Wisconsin.

- Breeding Habitat: Emergent Marsh, Northern Sedge Meadow and Marsh, Southern Sedge Meadow and Marsh.

- Nest: Mound of sedges, tubers, and other emergent vegetation surrounded by water (WDNR 2006).

- Nesting Dates: Eggs: early April to late May in Wisconsin (WDNR 2006).

- Foraging: Probes primarily in wetlands; also an agricultural opportunist.

- Migrant Status: Long-distance migrant; Florida population is resident.

- Habitat use during Migration: Natural or managed palustrine, lacustrine, and riverine wetlands, farm ponds, reclaimed surface mines, flooded agricultural fields, catfish production ponds, mountain reservoirs, and river sandbars (WDNR 2006).

- Arrival Dates: Early March to May in Wisconsin (WDNR 2006).

- Departure Dates: Late October to early December in Wisconsin; most birds depart mid-November (WDNR 2006).

- Winter Range: Wisconsin population winters in Tennessee, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina (WDNR 2006).

- Winter Habitat: Freshwater wetlands; forage during day in upland pastures with nearby water source (WDNR 2006).

- International Crane Foundation: http://www.savingcranes.org

- Migratory Whooping Crane Reintroduction: http://dnr.wi.gov/org/land/er/birds/wcrane/index.htm

- Operation Migration: http://operationmigration.org

- Whooping Crane Eastern Partnership: http://www.bringbackthecranes.org/

- Armbruster, M.J. 1990. Characterization of habitat used by whooping cranes during migration. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Biological Report 90(4). 16pp.

- Canadian Wildlife Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (CWS & USFWS). 2006. International recovery plan for the whooping crane (3rd revision). Ottawa: Recovery of Nationally Endangered Wildlife (RENEW), and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

- Drewien, R.C., J. Tautin, M.L. Courville, and G.M. Gomez. 2001. Whooping cranes breeding at White Lake, Louisiana, 1939: observations by John J. Lynch, U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey. Proc. N. Am. Crane Workshop 8: 24-30.

- Ehrlich, P.R., D.S. Dobkin, and D. Wheye. 1988. The birders handbook: a field guide to the natural history of North American birds. Simon & Schuster, Inc. New York.

- Gomez, G.M. 1992. Whooping cranes in southwest Louisiana: History and human attitudes. Proc. N. Am. Crane Workshop 6: 19-23.

- Kumlien, L. and N. Hollister. 1903. The birds of Wisconsin. Bulletin of the Wisconsin Natural History Society, 2: 1-143.

- Lewis, J.C. Whooping Crane (Grus americana). In The Birds of North America, No. 153 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, and The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C.

- Robbins, S.D. 1991. Wisconsin birdlife: population & distribution, past & present. Univ. of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI.

- Timoney, K.P. 1999. The habitat of nesting whooping cranes. Biological Conservation 89:189-197.

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). 2006. Wisconsin Whooping Crane Management Plan. PUBL-ER-650 06. Madison, WI. 86pp. http://dnr.wi.gov/org/land/er/birds/wcrane/pdfs/WC_Mgmt_Plan.pdf

- Compiler: Beth Kienbaum, Beth.Kienbaum@Wisconsin.gov

- Editor: Kim Kreitinger, K.Kreitinger@gmail.com

Photo by Arielle Shanahan, USFWS

Status/Protection

Population Information

As of August 1, 2007

Wild Population

Adult Pairs

Total

Aransas/Wood Buffalo

71

236

Florida non-migratory

17

44

Wisconsin Eastern Migratory Population

5

55

Subtotal

93

335

Captive Population

34

144

Total

127

479

Life History

Habitat Selection

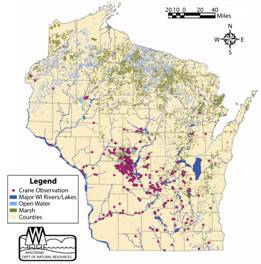

Although there are three distinct populations of Whooping Cranes, Wisconsin currently supports breeding pairs only from the Eastern Migratory Population (EMP). In 2001, the Whooping Crane Eastern Partnership began releasing captive-reared crane chicks at Necedah National Wildlife Refuge (NNWR) in central Wisconsin. NNWR was chosen based on the presence of suitable habitat, food resources, and favorable local attitudes (CWS & USFWS 2006). To date, Whooping Cranes typically use the shallow waters and emergent vegetation bordering the managed impoundments of NNWR but also use the palustrine and upland scrub-shrub, sedge meadow, and oak savannah habitats found there. Elsewhere in Wisconsin, cranes have been observed in 41 of 72 counties since 2001, primarily along major rivers and wetlands in the central and southern portions of the state (Figure 1). Lacustrine marshes, such as those associated with Puckaway, Rush, Yellowstone, and Poygan Lakes also are used. The exposed mudflats within these areas provide important food items, such as fish, amphibians, crustaceans, aquatic invertebrates, tubers, and rhizomes.

During migration, Whooping Cranes are opportunistic and readily exploit both wetland and upland habitats in Wisconsin. Roost sites often are located in wetlands, ranging from extensive, permanent wetlands to relatively small stock ponds. Palustrine, lacustrine, and riverine wetlands are used for foraging as well as grain fields, especially harvested cornfields (WDNR 2006). Both upland and wetland feeding sites often have excellent overhead and horizontal visibility with few visual obstructions (Armbruster 1990).

Habitat Availability

Habitat loss and degradation are implicated in the historic declines of the Whooping Crane. The conversion of native prairie to hay and grain fields made nearly all of their original breeding range unsuitable (CWS & USFWS 2006). Although historically considered an uncommon migrant in the south and the west of Wisconsin (Kumlien and Hollister 1903, Robbins 1991), it was essentially extirpated from the state by 1878.

Any wetland with minimal human disturbance, even small isolated wetlands, bears potential for use by Whooping Cranes. However, the locations of initial high concentration and nesting will probably occur in the primary rearing and release locations of central Wisconsin: Necedah National Wildlife Refuge, Mill Bluff State Park and Meadow Valley State Wildlife Area in Juneau County and surrounding wetlands of Monroe, Jackson, Wood, Marathon, Adams, and Marquette counties (for detailed site descriptions, see Appendix 8 in WDNR 2006).

Population Concerns

Although the Whooping Crane population size prior to Euro-American settlement is not known, some suggest an estimate of more than 10,000 individuals based on current densities and home range sizes expanded over the known historical distribution. By 1870 the population may have already been greatly reduced, with estimates of 500–1400 individuals (CWS & USFWS 2006). By 1944, only 21 birds remained in two small breeding populations: a non-migratory population inhabiting the area around White Lake, southwestern Louisiana and the migratory population that bred at Wood Buffalo National Park and wintered at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge (NWR). The non-migratory Louisiana population ceased breeding activities in 1939 (Gomez 1992, Drewien et al. 2001) and was extirpated by 1950, leaving the Aransas/Wood Buffalo population as the last remaining wild population (CWS & USFWS 2006).

The United States listed the Whooping Crane as endangered in 1970, followed by a Canadian listing in 1978. Consequently, the International Whooping Crane Recovery Team was established to oversee recovery objectives and strategies, including a recommendation to restore a migratory, self-sustaining Whooping Crane population in eastern North America (CWS & USFWS 2006). In 2001, the Whooping Crane Eastern Partnership began conditioning and reintroducing an experimental eastern migratory population of Whooping Cranes to follow an ultralight aircraft from central Wisconsin breeding grounds to Florida wintering grounds. Beginning autumn 2005, this program was supplemented with the direct release of captive and isolation-reared crane chicks into groups of Whooping or Sandhill Cranes. The chicks followed these birds from Wisconsin to the southern U.S. without ultralight guidance (WDNR 2006).

There are many threats to Whooping Cranes throughout their annual cycle. Collisions with power lines, towers, turbines and other structures are a significant cause of Whooping Crane mortality during migration. Human disturbances during the breeding season may cause them to leave an area. Hurricanes and drought can create problems on the wintering grounds. Because flocks are concentrated at only a few wintering locations, a catastrophic natural event can have devastating consequences to the population.

Recommended Management

For the next five years, the wild release conditioning program of Wisconsin will continue to add 20-30 Whooping Crane chicks to the experimental Eastern Migratory Population. To assure the sustainability of this population, the target 2020 interim goal is a minimum population of 100 Whooping Cranes with 25 breeding pairs that regularly nest and fledge offspring, in conjunction with the same target numbers for an introduced Florida non-migratory population. If the Florida reintroduction effort is unsuccessful, the EMP minimum target will become 120 Whooping Cranes with 30 breeding pairs that regularly nest and fledge offspring by 2020 (WDNR 2006).

Status reviews need to occur at five-year intervals starting in 2011 to identify opportunities and concerns regarding Whooping Crane management. Many government programs offer opportunities for Whooping Cranes conservation on private lands by providing financial incentives to restore or protect habitat. Examples include the Wetland Reserve Program (WRP) administered by the Natural Resource Conservation Service; the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) administered by the Farm Service Agency; Partners for Fish and Wildlife administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; and Habitat Restoration Areas administered by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. There also are many local habitat incentive programs available from non-governmental conservation groups like Ducks Unlimited and the Wisconsin Waterfowl Association (WDNR 2006).

Because utility line collisions pose a threat to Whooping Cranes in Wisconsin, hazardous sections of power lines within frequently used areas should be marked with visibility markers to reduce collision potential. Also, future line corridors should avoid wetlands or other crane use areas (WDNR 2006).

Research Needs

Factors contributing to nest abandonment in the EMP require more study. Nest cameras may help to identify sources of disturbance. More data on EMP breeding habitat characteristics, home range size, and spatial distribution would guide future land management and acquisition efforts. A state assessment of the distribution, abundance, conditions, and ownership of wetlands and other important wetland bird habitats also would aid management. Basic information on nesting ecology of EMP Whooping Cranes is relatively unknown and warrants study (WDNR 2006).

More research is needed to determine mortality risk factors. The Whooping Crane Eastern Partnership Health Team is currently analyzing the first five years of health data, assessing disease prevention and control strategies, and investigating the potential impacts of emerging diseases (e.g., avian influenza and West Nile virus). However, future research is needed to reduce the impacts of musculoskeletal and other diseases on the survivorship and fitness of captive-reared chicks.

Information Sources

References

Contact Information