Photo by Paul Carson

Status/Protection

- Global Rank: G5 Key to global and state ranks

- State Rank: S5B

- WBCI Priority: PIF

Population Information

The Federal BBS information can be obtained at http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html by clicking on Trend Estimates and selecting the species in question. All estimates are for time period (1966-2005).

Note: The cyclic nature of Ruffed Grouse populations in northern latitudes complicates interpretation of trends for these populations (Dessecker and McAuley 2001). The BBS may not be the appropriate method for detecting long-term trends for Ruffed Grouse.

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey: significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (WI): significant increase

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 23): non-significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 12): non-significant decline

- WSO Checklist Project: stable (1983-2007)

- Wisconsin Drumming Survey: -10% decrease statewide from 2004 to 2005. Roadside drumming counts have been conducted in Wisconsin annually since 1964 and provide statewide population indices (Dhuey 2005). Indices show a declining trend in Ruffed Grouse populations over 40 year period.

Life History

- Breeding Range: Alaska east across Canada and the northern U.S. to the Atlantic Coast, extending south along coast and into the Appalachian states (Rusch et al. 2000).

- Breeding Habitat: Aspen, Oak, Shrub-carr, Alder Thicket, Jack Pine, Forested Ridge and Swale.

- Nest: Bowl-like depression in dead leaves and vegetation usually found at the base of a tree or stump.

- Nesting Dates: Late April through mid-June.

- Foraging: Young are ground foragers eating mainly insects and other small invertebrates. Adults are browsers, primarily vegetarians, eating herbaceous plants (especially in spring and summer), seeds, fruits (especially in fall and winter), nuts, flowers, buds, and leaves of trees and shrubs. In many areas, aspen, birch, or hazelnut buds and catkins are important food resources in winter and spring (Barber et al. 1989).

- Migrant Status: Year-round Resident.

- Habitat use during Migration: N/A

- Arrival Dates: N/A

- Departure Dates: N/A

- Winter Range : In close proximity to their summer range.

- Winter Habitat: If snow is deep enough (greater than 10 inches), Ruffed Grouse will snow roost to stay warm and out of danger. In low snow years or in the southern part of its range, Ruffed Grouse will often roost in conifers to reduce heat loss (Runkles and Thompson 1989). Flower buds found on mature male aspen trees are a very important food source for Ruffed Grouse during winter and early spring.

Habitat Selection

Ruffed Grouse are early successional forest specialists. Optimum habitats for Ruffed Grouse include young (6 to 15 year old), even-age deciduous stands that typically support 20-25,000 woody stems/ha (Kubisiak 1985). Although commonly identified as an “edge” species, Ruffed Grouse typically avoid hard-contrast edges (Gullion 1984). Dense young forest stands are especially important to drumming males in the spring. Male grouse select an elevated platform, usually a large downed log, for their drumming display. Nesting habitat includes pole-sized stands with open understories and a dense overstory (Rusch et al. 2000). Ruffed grouse broods are seldom found far from dense cover. Quality brood habitat includes small forest openings with a substantial shrub component (Dessecker and McAuley 2001). Ruffed Grouse use young stands of many different deciduous forest types (ie, aspen, birch, oak-hickory) across their range. However, aspen forests can support population densities that greatly exceed those attained in other forest communities (Thompson and Dessecker 1997). Young deciduous forest and shrub-dominated old field habitats protect Ruffed Grouse from predators throughout the year. To meet their needs, Ruffed Grouse generally seek upland forests containing a high density of shrubs taller than 1.5 meters, and tree seedling, saplings, and sprouts taller than 4.5 meters all within 300 feet of a good food resource. Habitats with good vertical structure provide shelter for Ruffed Grouse while making them less accessible to predators (Kubisiak 1985).

Habitat Availability

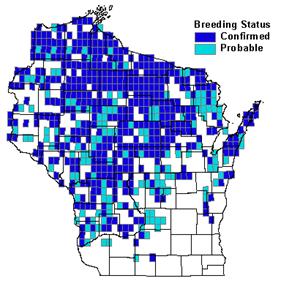

Ruffed Grouse breed where appropriate habitat is found throughout Wisconsin in all but the southeastern corner of the state (Robbins 1991). Highest concentrations were reported during the Breeding Bird Atlas project in the Central Sand Plains, Forest Transition, Northwest Lowlands, North Central Forest, Northern Highland, and Northeast Sands Ecological Units. Within these units, the Chequamegon/Nicolet National Forest, Northern Highland/American Legion State Forest, Flambeau State Forest, Black River State Forest, Peshtigo River State Forest, Kettle Moraine State Forest, Mead Wildlife Area, Douglas, Florence, Jackson, Lincoln, Marinette, Oneida, Price and Sawyer County Forests appear to be important breeding areas. Industrial lands, especially in Northern Wisconsin, with an emphasis on early successional deciduous species also provide important habitat for this species.

Young forest or shrubland habitats, critical to Ruffed Grouse, are declining throughout Wisconsin. Recent forest inventories conducted in Wisconsin (1983 and 1996) showed an 8% decline in the aspen-birch forest type across the state and a 36% decline in Central Wisconsin alone during this period. In Northern Wisconsin, aspen-birch forest type is the most common early successional community; however between 1936 and 1996, aspen-birch types declined from 5.2 million acres to 3.2 million, a 40% decline (WDNR 1997).

Population Concerns

Habitat loss and degradation are the predominant factors affecting Ruffed Grouse population trends. Declines in young forest habitats and the isolation of these habitats in some landscapes may be limiting Ruffed Grouse recruitment and therefore population densities (Dessecker and McAuley 2001). In SW Wisconsin, a rapid decline of Ruffed Grouse populations since the mid-1980’s has occurred and has most likely been the result of forest maturation, isolation of quality habitat and a large predator base (Walter 2005). The farther grouse have to travel between food and cover, the fewer the grouse (Barber et al. 1989). Across the state Ruffed Grouse populations continue to decline with the last cyclic peak in 1999 much lower than those of the previous three cycles (Dhuey 2005). The abrupt cyclic declines in Minnesota and Wisconsin are consistently associated with the influx of raptors, primarily Northern goshawk and great horned owls, whose invasions are triggered by cyclic declines of snowshoe hares in Canada (Rusch et al. 2000). Predation and weather related factors on young grouse through September largely determine annual rates of increase (Keith and Rusch 1989).

Recommended Management

Early successional habitats, essential for Ruffed Grouse, are by nature ephemeral. Management efforts which achieve greater age class interspersion while maintaining aspen and aspen-alder habitat should be encouraged for Ruffed Grouse. On landscapes where it is impractical to allow the return of natural or prescribed fires, commercial timber harvests or other habitat management practices should be implemented at regular intervals (approximately every 10 years) to ensure a continuous supply of quality Ruffed Grouse habitat on the landscape. Even-age silvicultural systems (clearcut, seed tree or shelterwood) are the most appropriate harvest methods to create Ruffed Grouse habitat. These methods remove sufficient canopy from the parent stand to result in enough understory development to provide protective cover for Ruffed Grouse. (Dessecker and McAuley 2001)

Research in aspen forests managed on a 40-year rotation shows that small harvest units (1-2 ha.) are more beneficial to Ruffed Grouse than larger harvest units (Gullion 1984). The small harvest units are designed to provide Ruffed Grouse with patches of protective cover (6 to 15 year old stands) interspersed with mature stands that provide male flower buds for grouse during winter. If larger cuts (greater than 40 acres) are the only alternative, clones of 50-60 mature aspen should be retained in every 20 acres. The Ruffed Grouse Society recommends 5 to 20 acre patches of young, middle-aged and mature aspen, all within close proximity to one another. Research at the Sandhill Wildlife Area showed that maintaining 30-35% of the aspen type in sapling-sized stands under 26 years old produced higher sustained yields of Ruffed Grouse. Densities of drumming males were 1.6 times higher on managed areas than on unmanaged areas 10 years following harvest, and after 12 years doubled on managed areas (Kubisiak 1985).

Management of oak habitats for Ruffed Grouse should include the following: (1) Conduct shelterwood cuts or clearcuts of 20 acres or less, leaving designated groups or scattered oaks (residual basal area less than 20 square feet). (2) Encourage habitat diversity where oaks occur in mixed stands with aspen, pine, or other hardwoods. (3) Prescribed burning (preferably in the spring) may also be an effective tool in selected oak stands to stimulate sprouting of understory woody vegetation and encourage oak regeneration (Kubiasiak 1985). In hilly terrain, young oak forests growing on north or east facing slopes tend to provide the best habitat for Ruffed Grouse. These slopes are not exposed to the heat of the sun and stay relatively cool and moist and often support succulent food sources.

In areas of the state where snow depths are generally less than 7 or 8 inches, planting small patches of densely needled conifers like white spruce can enhance Ruffed Grouse survival in the winter.

Research Needs

While Ruffed Grouse population dynamics are fairly well understood, most research to date has been conducted in northern, aspen-dominated forests. The factors which limit grouse populations in more southern, oak-dominated forests (such as Southwest Wisconsin) is poorly understood. An ongoing research project in Richland County is using radio telemetry to evaluate Ruffed Grouse population dynamics in SW Wisconsin (Walter 2005). Implementation of targeted silvicultural treatments in SW Wisconsin and follow-up evaluations of the Ruffed Grouse population response to management activities is needed. Kubisiak (1985) suggested that research was needed to refine the ability to predict grouse numbers with various levels of habitat management and better define the upper limits of conifer cover to grouse habitat quality.

Forestry practices have changed over the years with a greater use of new silvicultural techniques such as green tree retention, small patch cuts, and shelterwoods. Research on how grouse respond to these various practices may help us better manage grouse habitat. Other research may include the role of predators on the grouse cycle, influence of fragmentation on brood habitat, and the role of conifers in winter.

Continue to monitor Ruffed Grouse population trends statewide through drumming counts and harvest surveys. Long term Ruffed Grouse monitoring data on the Stone Lake Experimental Area near Rhinelander needs to be analyzed.

Information Sources

References

- Barber, H.L., F.J. Brenner, R. Kirkpatrick, F.A. Servello, D.F. Stauffer and F.R. Thompson. 1989. The kingdom of the Ruffed Grouse – Food. Pages 268 - 283 in The Wildlife Series - Ruffed Grouse, ( S. Atwater and J. Schnell, Eds.) Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, PA.

- Dessecker, D.R. and D.G. McAuley. 2001. Importance of early successional habitat to Ruffed Grouse and American woodcock. Wildlife Society Bulletin. 29(2):456-465.

- Dhuey, B. 2005. Ruffed Grouse drumming survey 2005. Pages 6 – 9 in Wisconsin wildlife surveys – August 2005 (J. Kitchell and B. Dhuey, Eds.) Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, W.

- Gullion, G.W. 1984. Managing northern forests for wildlife. Ruffed Grouse Society, Coraopolis, Pennsylvania.

- Keith, L.B. and D.H. Rusch. 1989. Predator’s role in the cyclic fluctuations of Ruffed Grouse. Acta Congress International Ornithology 19:699-732.

- Kubisiak, J.F. 1985. Ruffed Grouse habitat relationships in aspen and oak forests of central Wisconsin. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Technical Bulletin 151, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Robbins , S.D. 1991. Wisconsin birdlife: population & distribution, past & present. Univ. of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Ruffed Grouse Society. Managing Your Aspen Forests for Ruffed Grouse.

- Rusch, D.H., S. Destefano, M.C. Reynolds, and D. Lauten. 2000. Ruffed Grouse, Bonasa umbellus. No. 515 in Gill, F., and Poole, A. (Eds.). The Birds of North America. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, PA, and The American Ornitologists’ Union, Washington, D.C., USA.

- Runkles, R.R. and F.R. Thompson. 1989. The pattern of life – Snow roosting. Pages 161 - 164 in The Wildlife Series - Ruffed Grouse, ( S. Atwater and J. Schnell, Eds.) Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

- Thompson, F.R. and D.R. Dessecker. 1997. Management of early-successional communities in central hardwood forests. United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service General Technical Report NC-195, St. Paul, Minnesota.

- Walter, S.E. 2005. Ecology of Ruffed Grouse in southwest Wisconsin – Progress report for cooperating landowners. University of Wisconsin, Richland Center, Wisconsin. 12 pp.

- WDNR. 1997. A look at Wisconsin forests. PUB-FR-122. Madison, Wisconsin.

Contact Information

- Compiler: Gary Zimmer, 715-674-7505, rgszimm@newnorth.net

- Editor: Gary Zimmer, 715-674-7505, rgszimm@newnorth.net