Photo by Scott Franke

Status/Protection

- Global Rank: G4 Key to global and state ranks

- State Rank: S2B

- WBCI Priority: SGCN, PIF, State Special Concern

Population Information

Federal BBS information can be obtained at http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html by clicking on Trend Estimates and selecting the species in question. All estimates are for 1966-2005.

*Note: There are important deficiencies with these data. These results may be compromised by small sample size, low relative abundance on survey route, imprecise trends, and/or missing data. Caution should be used when evaluating this trend.

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey: significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (WI): non-significant decline*

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 23): non-significant increase*

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 12): significant decline

- Nicolet National Forest Bird Survey (UWGB): significant decline (Howe and Roberts 2005)

- WSO Checklist Project: stable (1983-2007)

Life History

- Breeding Range: Alaska east across Canada and northern U.S. to the Atlantic Coast; south into the mountainous regions of the western U.S. (Altman and Sallabanks 2000).

- Breeding Habitat: Black Spruce, Swamp Conifer-Balsam Fir, Tamarack, White Cedar, Open Bog-Muskeg, Forested Ridge and Swale; occasionally found in clearcuts.

- Nest: Cup; nest height ranges from 1.5-34 meters above ground (Altman and Sallabanks 2000).

- Nesting Dates: Eggs: mid to late June (WSO 1995).

- Foraging: Hawks (Ehrlich et al. 1988).

- Migrant Status: Neotropical migrant.

- Habitat use during Migration: Coniferous and deciduous open woodlands, riparian areas, woodland and forest edge, openings (Altman and Sallabanks 2000).

- Arrival Dates: Mid-May to mid-June (Robbins 1991).

- Departure Dates: Early August to mid-September (Robbins 1991).

- Winter Range: Venezuela, Columbia, Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Brazil (DeGraaf and Rappole 1995).

- Winter Habitat: Woodland and forest edges and openings, most often in mature conifer forests between 700-3400 meters in elevation (Altman and Sallabanks 2000).

Habitat Selection

The Olive-sided Flycatcher inhabits coniferous forests, especially those with openings created by beaver ponds, meadows, streams or rivers, burns, or clearcuts. In Wisconsin this flycatcher occurs in spruce-tamarack bogs and swamps, and less often in northern white cedar forests (Robbins 1991, Epstein 2006) and pine barrens. When found in early-successional forest, Olive-sided Flycatchers choose areas with remaining large trees or snags often at the edges of lakes, streams, or bogs (Altman and Sallabanks 2000). They frequently perch at or near the top of a tall tree or snag, sallying out to capture flying insects and returning to the same perch (Altman and Sallabanks 2000, Askins 2000). Nests are located on the outer portion of branches, 1.5 - 34 meters above ground, often under an overhanging branch (Altman and Sallabanks 2000).

Habitat Availability

This species is found primarily in the northernmost counties in Wisconsin (Epstein 2006). Black spruce and other coniferous lowland forest types used by Olive-sided Flycatchers were widespread and relatively common historically, although they did not typically occur in large patches in Wisconsin. These forest types remain relatively common in much of their Wisconsin range today (WDNR 2005). However, beaver control programs in northern Wisconsin may reduce the habitat suitability in some areas. Within the Great Lakes region, coniferous lowland forests may have declined by as much as 15% (Snetsinger and Ventura n.d.).

Population Concerns

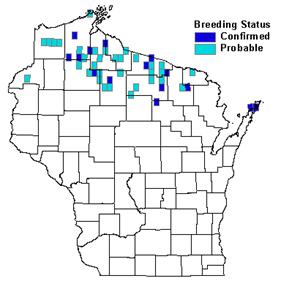

Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data suggest significant declines for this species range-wide. BBS data for Wisconsin suggest non-significant declines; however, these results are difficult to interpret due to small sample sizes (Sauer et al. 2005). This species was not commonly encountered on the Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas either. During the six-year period (1995-2000) of the Atlas, observers documented probable or confirmed breeding status in just 4% of the surveyed quads. Low breeding confirmation during the Atlas may be attributed to the difficulty of observing nests, difficult access to breeding territories, and the overall low densities of this species in apparently suitable habitat (Epstein 2006).

In the West, numerous studies report positive numerical responses of Olive-sided Flycatchers to some types of timber harvest practices. Given this response, and that there is an increasing amount of harvested forests on the landscape, it is perplexing that Olive-sided Flycatcher populations continue to decline. Perhaps some harvested sites act as sink habitats, resulting in reduced reproductive success due to lower food availability, higher rates of Brown-headed Cowbird parasitism, and other factors. However, the breeding range of the Olive-sided Flycatcher encompasses a large area, subject to many different forest management regimes. Its persistent decline across this diverse landscape suggests it may be more limited by habitat loss or alteration on the wintering grounds (Altman and Sallabanks 2000).

Recommended Management

Few data exist on the impacts of timber harvesting or other forest management practices on this species in Wisconsin. Specific management prescriptions are difficult to develop without these data. In general, protecting coniferous forests, maintaining natural patterns of forest fire that create suitable forest openings, and retaining snags are practices that will likely benefit Olive-sided Flycatchers in Wisconsin (WDNR 2005). Like other species that use burned forests, Olive-sided Flycatchers may suffer from the effects of overzealous “salvage logging” in these locations (Altman and Sallabanks 2000). Addressing habitat loss on the wintering grounds should be a high priority since it is unclear if this is the primary limiting factor of Olive-sided Flycatcher populations. Conservation and management strategies for this species should be focused in the following Wisconsin ecological landscapes: North Central Forest, Northern Highland, Northern Lake Michigan Coastal, Northwest Lowlands, and Northwest Sands (WDNR 2005). Within these landscapes, key conservation sites include Upper Brule River in Douglas County and the Headwaters Wilderness Area.

Research Needs

More information is needed on nesting success, food availability, predation rates, and competition in different forest types and management regimes. Information is urgently needed on the impacts of fragmentation and habitat loss on the wintering grounds (Altman and Sallabanks 2000). In Wisconsin, targeted surveys in appropriate habitat would better elucidate the Olive-sided Flycatcher’s population status in the state.

Information Sources

- Chequamegon National Forest Bird Survey (NRRI) species account: http://www.nrri.umn.edu/mnbirds/accounts/OSFLa2.htm

- Chequamegon National Forest Bird Survey (NRRI) map: http://www.nrri.umn.edu/mnbirds/accounts/OSFLm2.htm

- Nicolet National Forest Bird Survey Map: http://www.uwgb.edu/birds/nnf/species/OSFL.htm

- North American Breeding Bird Survey: http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html

- Temple S.A., J.R. Cary, and R. Rolley. 1997. Wisconsin Birds: A Seasonal and Geographical Guide. Wisconsin Society of Ornithology and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI.

- Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas: http://www.uwgb.edu/birds/wbba/

References

- Altman, B and R. Sallabanks. 2000. Olive-sided Flycatcher (Contopus cooperi). In The Birds of North America, No. 502 (A.Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

- Askins, R.A. 2000. Restoring North America’s birds: lessons from landscape ecology. Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CN.

- Ehrlich, P.R., D.S. Dobkin, and D. Wheye. 1988.The birders handbook: a field guide to the natural history of North American birds. Simon & Schuster, Inc. New York.

- Epstein, E. 2006. Olive-sided Flycatcher. In Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Wisconsin. (N.J. Cutright, B.R. Harriman, and R.W. Howe, eds.) The Wisconsin Society for Ornithology, Inc. 602pp.

- Howe, R.W. and L.J. Roberts. 2005. Sixteen years of habitat-based bird monitoring in the Nicolet National Forest. In C.J. Ralph and T.D. Rich, editors. Bird Conservation Implementation and Integration in the Americas: Proceedings of the Third International Partners in Flight Conference. 2002 March 20-24; Asilomar, California, Volume 2. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-191. Albany, CA: Pacific Southwest Research Station, Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; 643 p.

- Robbins, S.D. 1991. Wisconsin birdlife: population & distribution, past & present. Univ. of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI.

- Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, and J. Fallon. 2005. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2005. Version 6.2.2006. USGS Patuxent Wildlife ResearchCenter, Laurel, MD.

- Snetsinger, S. and S. Ventura. n.d. Landcover change in the Great Lakes region from mid-nineteenth century to present. Online at http://www.ncrs.fs.fed.us/gla/

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). 2005. Wisconsin’s Strategy for Wildlife Species of Greatest Conservation Need. Madison, WI.

Contact Information

- Compiler: William P. Mueller, iltlawas@earthlink.net

- Editors: Kim Kreitinger, K.Kreitinger@gmail.com |

Randy Hoffman, Randolph.Hoffman@Wisconsin.gov