Photo by Ryan Brady

Status/Protection

- Global Rank: G5 Key to global and state ranks

- State Rank: S4B

- WBCI Priority: PIF

Population Information

Federal BBS information can be obtained at http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html by clicking on Trend Estimates and selecting the species in question. All estimates are for 1966-2005.

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey: significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (WI): significant increase

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 23): N/A

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 12): N/A

- Chequamegon National Forest Bird Survey (NRRI): significant decline (1992-2005)

- Nicolet National Forest Bird Survey (UWGB): significant decline (Howe and Roberts 2005)

- WSO Checklist Project: significant increase (1983-2007)

Life History

- Breeding Range: Northeastern British Columbia east across southern Canada and Great Lake states to the Atlantic Coast (Pitocchelli 1993).

- Breeding Habitat: Shrubbery and bushes of open deciduous woodland and shrubby margins of bogs, swamps and marshes (AOU 1983); Oak, Aspen, Alder Thicket, Shrub-Carr.

- Nest: Cup, usually on or near ground (Pitocchelli 1993).

- Nesting Dates: Eggs: Late May to early July (Robbins 1991).

- Foraging: Foliage glean, ground glean (Ehrlich et al. 1988).

- Migrant Status: Neotropical migrant.

- Habitat use during Migration: Not well known; uses dense understory vegetation, shrubs (Pitocchelli 1993).

- Arrival Dates: Early May to early June (Robbins 1991).

- Departure Dates: Early August to late September (Robbins 1991).

- Winter Range: Southern Nicaragua, Panama, Columbia, Venezuela, Ecuador (DeGraaf and Rappole 1995).

- Winter Habitat: Moist thickets, grasses, shrubs, unused pasture, high-elevation thickets (Pitocchelli 1993).

Habitat Selection

The Mourning Warbler nests in disturbed second-growth forests containing a dense understory of deciduous shrubs, saplings, and herbs (Epstein 2006). Natural disturbance events such as windstorms and fire as well as certain logging activities often provide the structural features required by this species (Pitocchelli 1993, Askins 2000, Epstein 2006). Common features of Mourning Warbler habitat include a thick shrub layer, relatively open tree canopy, and high volume of coarse woody debris (Burris and Haney 2005). Upland forest and shrub habitats tend to be favored over lowland habitats in Wisconsin (Epstein 2006). In the Nicolet National Forest, Howe et al. (1996) reported that Mourning Warbler preferred aspen/birch forest types and avoided hemlock and jack pine types. However, Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas records documented Mourning Warblers using a wide variety of forest and shrub types (Epstein 2006). The Mourning Warbler prefers relatively large tracts of habitat and is considered to be area sensitive (Freemark and Collins 1992). Temple (1988) estimated 65 hectares to be the minimum size required for 50% occupancy in southern Wisconsin. Nest are located on or <1 meter above the ground, often in ferns, clumps of grass, or thorn-bearing shrubs such as blackberries (Pitocchelli 1993).

Habitat Availability

The early successional habitats favored by this species are increasingly threatened by human development. This is especially concerning in southern Wisconsin where agricultural and urban expansion has limited suitable habitat to just a few scattered locations, including the Baraboo Hills (Mossman and Lange 1982), Kettle Moraine State Forest, and Jackson “Marsh” in Washington County (R.C. Domagalski, pers. comm.). In central Wisconsin, this species is mostly associated with county forests and state wildlife management areas in Eau Claire, Buffalo, Jackson, Trempaleau, Marathon, Waupaca, and Shawano counties. In the extensive forests of northern Wisconsin, early-successional habitats are less limited due to the prevalence of logging activities in the region. The Chequamegon/Nicolet National Forest, Northern Highland/American Legion State Forest, Menomonie Indian Reserve, and Douglas, Lincoln, and Marinette county forests are important breeding areas.

Population Concerns

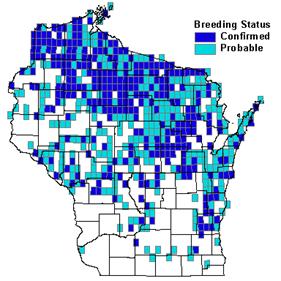

Population trends for this species are difficult to interpret and sometimes contradictory within the same region. Breeding Bird Survey data suggest a significant decline range-wide and significant increase in Wisconsin (Sauer et al. 2005). The Chequamegon and Nicolet National Forest Bird Surveys indicate significant annual declines, but the Wisconsin checklist project suggests a significant increase (Rolley 2005, Danz et al. 2007). Robbins (1991) cited this species as being a fairly common summer resident in northern Wisconsin and uncommon to rare elsewhere in the state. Recent Breeding Bird Atlas work also documented fewer breeding attempts in southern Wisconsin compared to the north. Atlas observers confirmed breeding in approximately 27% of the quads surveyed from 1995-2000 (Epstein 2006).

Mourning Warbler populations may be negatively impacted by forest fragmentation, forest maturation, and urbanization. Human development resulted in the loss of suitable habitat in most of southern Wisconsin and remains a concern for northern Wisconsin. However, some human activities such as logging, road building in forested areas, and other activities that create clearings in closed-canopy forests may actually benefit this species (Pitocchelli 1993).

Recommended Management

The Mourning Warbler benefits from forest clearing and management that promotes dense growth of young trees and shrubs. Managers should maintain early-successional vegetation across a variety of forest types and ownerships. In areas prioritized for early-successional species, clearcuts and other intensive harvest methods that result in significant regeneration of deciduous species, i.e., group selection and shelterwood cuts, are expected to provide favorable habitat (Schulte and Niemi 1998, Askins 2000). In southern Illinois, Robinson and Robinson (1999) reported that the creation of canopy gaps through selection cutting of mixed hardwood forests can provide habitat for shrub-associated species from one to five years post-harvest, rarely up to 11 years post-harvest. Managers should maintain some snags, large living trees, downed logs, and coarse woody debris in logged areas to promote the structural complexity beneficial to a range of species including the Mourning Warbler (Askins 2000). Powerline corridors within a forested landscape may provide suitable breeding habitat if managed for a thick shrub layer (Askins 2000). Herbicide application and brush clearing in these areas should be avoided during the breeding season. Conservation and management strategies for this species should be focused in the following ecological landscapes in Wisconsin: the Northwest Lowlands, North Central Forest, Northern Highlands, Northeast Sands, and Northern Lake Michigan Coastal.

Research Needs

More information is needed on factors affecting reproductive success including cowbird parasitism (Pitocchelli 1993). In Wisconsin, more research on breeding densities and reproductive success among forest types may help guide future management efforts. Also, studies investigating minimum patch size requirements within these landscapes are needed.

Information Sources

- Chequamegon National Forest Bird Survey (NRRI) species account: http://www.nrri.umn.edu/mnbirds/accounts/MOWAa2.htm

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology species account: http://www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/BirdGuide/Mourning_Warbler.html

- Great Lakes Bird Conservation probability map: http://www.uwgb.edu/birds/greatlakes/species/mowamap2.htm

- Nicolet National Forest bird survey species map: http://www.uwgb.edu/birds/nnf/species/MOWA.htm

- North American Breeding Bird Survey http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov

- Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas http://www.uwgb.edu/birds/wbba/

References

- American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU). 1983. Check-list of Birds. Sixth edition. AOU, Allen Press, Inc. Lawrence, Kansas.

- Askins, R.A. 2000. Restoring North America’s birds: lessons from landscape ecology. Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CN.

- Danz, N.P., G.J. Niemi, J. Lind, and J.M. Hanowski. 2007. Birds of Western Great Lakes Forests. http://www.nrri.umn.edu/mnbirds.

- DeGraaf, R.M.and J.H. Rappole. 1995. Neotropical migratory birds: natural history, distribution, and population change. Comstock Publ. Assoc., Cornell Univ. Press, Ithaca, NY.

- Ehrlich, P.R., D.S. Dobkin, and D. Wheye. 1988. The birders handbook: a field guide to the natural history of North American birds. Simon & Schuster, Inc. New York.

- Epstein, E. 2006. Mourning Warbler. In Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Wisconsin. (N.J. Cutright, B.R. Harriman, and R.W. Howe, eds.) The Wisconsin Society for Ornithology, Inc. 602pp.

- Freemark, K. and B. Collins. 1992. Landscape ecology of birds breeding in temperate forest fragments. Pp. 443 – 454 in Ecology and conservation of neotropical migrant landbirds. (J.M. Hagan and D.W. Johnston, eds.) Smithsonian Instituition Press, Washington and London.

- Hoffman. R.M. 1989. Birds of Wisconsin’s northern mesic forests. Pass. Pigeon 51(1): 97-110.

- Howe, R.W., G. Niemi and J.R. Probst. 1996. Management of western Great Lakes forests for the conservation of neotropical migratory birds. Pages 144-167 in F.R. Thompson, III, ed. Management of midwestern landscapes for the conservation of neotropical migratory birds. U.S. For. Serv. Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-187. North Central For. Exp. Sta., St. Paul, MN.

- Niemi, G. and J. Hanowski. 1984. Relationships of breeding birds to habitat characteristics in logged areas. Journal of Wildlife Management 48:438-443.

- Pitocchelli, J. 1993. Mourning Warbler (Oporornis philadelphia). In The Birds of North America, No. 72, (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, PA, and the American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C.

- Robbins, S.D. 1991. Wisconsin birdlife: population & distribution, past & present. Univ. of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI.

- Rolley, R. 2005. Wisconsin Checklist Project. http://dnr.wi.gov/org/land/wildlife/harvest/reports/07checklist.pdf

- Schulte, L.S. and G.J. Niemi. 1998. Bird communities of early-successional burned and logged forest. Journal of Wildlife Management 62: 1418-1429.

- Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, and J. Fallon. 2005. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2005. Version 6.2.2006. USGS Patuxent Wildlife ResearchCenter, Laurel, MD.

- Temple, S.A. 1988. When is a bird’s habitat not habitat? Passenger Pigeon 50(1): 37-41.

Contact Information

- Compiler: William P. Mueller, iltlawas@earthlink.net

- Editors: Kim Kreitinger, K.Kreitinger@gmail.com | Gary Zimmer, rgszimm@newnorth.net