Photo by Ryan Brady

Status/Protection

- Global Rank: G5 Key to global and state ranks

- State Rank: SNAB, S3N

- WBCI Priority: SGCN, WFOWL, State Special Concern

Population Information

The Federal BBS information can be obtained at http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html by clicking on Trend Estimates and selecting the species in question. All estimates are for time period (1966-2005).

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey: non-significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (WI): N/A

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 23): N/A

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 12): N/A

- Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Survey: decline (1955-2005) (USFWS 2006)

- WSO Checklist Project: inverted u-shaped trend (1983-2007)

Life History

- Breeding Range: Alaska east across Canada to Ontario south into Great Basin and northern Great Plains states (Austin et al. 1998).

- Breeding Habitat: Inland Open Water.

- Nest: Scrape in tall vegetative cover or on floating vegetation (Austin et al. 1998)

- Nesting Dates: Late May to mid-July (Austin et al. 1998).

- Foraging: Surface dives (Ehrlich et al. 1988).

- Migrant Status: Short-distance migrant.

- Habitat use during Migration: Northern Sedge Meadow and Marsh, Emergent Marsh, Inland Open Water, Great Lakes Open Water; larger permanent and semi-permanent wetlands, lakes and large impounded portions of rivers, flooded croplands; may use smaller wetlands and marshes during spring migration (Austin et al. 1998).

- Arrival Dates: Mid-March in spring; mid-September in fall (Robbins 1991).

- Departure Dates: Late May in spring; late December in fall (Robbins 1991), although known to winter on Lake Michigan.

- Winter Range: Atlantic Coast from New Jersey south; along Louisiana and Florida Gulf Coasts; Pacific Coast from Alaska south to Mexico; Great Lakes of upper Midwest (Austin et al 1998).

- Winter Habitat: Mainly found along shores of lakes, reservoirs, and fresh to brackish coastal bays and estuaries of south Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific coasts (Austin et al. 1998), however, present throughout the lower Great Lakes during winters with open water.

Habitat Selection

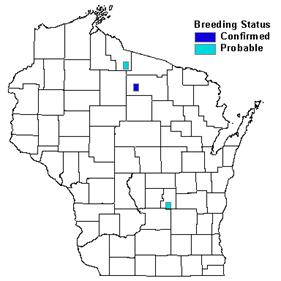

Wisconsin does not sustain a regular breeding population of Lesser Scaup, but this species is abundant during spring and fall migration and winters on Lake Michigan (Petersen et al. 1982, Robbins 1991). In autumn, Lesser Scaup use large permanent and semi-permanent wetlands and lakes, including the Great Lakes and large impounded portions of the Upper Mississippi River (Austin et al. 1998). In the spring, they tend to use smaller wetlands and flooded croplands that are typically overflown in the fall (Bellrose 1976, Austin et al. 1998). Scaup habitat use and distribution are strongly correlated with the availability of preferred food resources, such as amphipods and other aquatic invertebrates (Custer and Custer 1996). In particular, the proliferation of zebra mussels, an introduced species from Central Europe, may be altering movement patterns of Lesser Scaup in the Great Lakes (Petrie and Schummer 2002). Zebra mussels occur in extremely high densities within the lower Great Lakes and provide an easy food source for many species of diving ducks. In recent years, Lesser Scaup numbers have increased dramatically in areas colonized by zebra mussels. Unfortunately, the apparent benefits of this readily available food source may be negated by the threat of food contamination (i.e., bioaccumulation of toxins).

Habitat Availability

Two major migration corridors exist within Wisconsin, including one following the Mississippi River in the western part of the state and the other crossing the state from the west to the east (Jahn and Hunt 1964, Belrose 1976). The Upper Mississippi River (UMR) pools 7-9 are important staging areas, including Lake Onalaska near La Crosse, Wisconsin. Lesser Scaup also occur throughout Lake Superior’s Chequamegon Bay, the St. Croix Valley, the impounded portions of Crex Meadows, Green Bay and surrounding waters, Lake Michigan, George W. Mead, Grand River Marsh, and Horicon Marsh wildlife areas, (Fannes 1981, Wheeler et al. 1984, WDNR 1992). Important inland lakes for migrating Lesser Scaups include Winnebago, Poygan, Buttes des Morts, Winneconne, Koshkonong, Petenwell Flowage, and Castle Rock (Jahn and Hunt 1964, Kahl 1991, Robbins 1992, WDNR 1992).

Several factors threaten the continued availability and suitability of staging habitats in the state. The drainage and conversion of wetlands reduces the quality and quantity of stopover habitat available (Austin et al. 1998). Increased sedimentation, the proliferation of invasive species, and fish introductions into historically fish-free wetlands have the potential to reduce availability and quality of scaup food resources across a large landscape (Kahl 1991, Austin et al. 1998, Austin et al. 1999, Anteau and Afton 2004). Excessive human disturbances, such as recreational boating, also can reduce the suitability of staging areas to migrating waterfowl (Korschgen et al. 1985, Kahl 1991).

Population Concerns

The continental population of scaup (lesser and greater combined) has precipitously declined over the past 20 years. The 2006 Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Survey data indicate scaup numbers 37% below the long-term average (1955-2005) and a record low scaup population estimate (USFWS 2006). However at approximately 3.3 million breeding birds, it is still the 3rd to 4th most abundant duck in this continental waterfowl survey. Aerial waterfowl survey data from the UMR pools consistently show fall concentrations of >40,000 staging Lesser Scaup, but significant annual fluctuations obscures any obvious trend. Fall migration numbers ranged from a 1997 peak estimate of 41, 265 to a 2003 peak estimate of 144,120 with an eleven-year peak average of 108,000 (USFWS 2006).

Several theories are being investigated to account for this long-term population decline, including climate change impacts on breeding grounds, degradation of spring migration habitat, and contaminant impacts on productivity and survival. A landscape-scale decline in the availability and quality of forage may be impacting scaup populations (Anteau 2002) and making them more reliant on several exotic species. In particular, zebra mussels have become an important food item but may contribute to contaminant uptake and bioaccumulation in feeding birds (Custer and Custer 1996, Austin et al. 1999). Faucet snails occur in several important staging areas in Wisconsin and can carry trematode parasites harmful to Lesser Scaup. When ingested, snails infected with this parasite can cause massive die-offs of Lesser Scaup and other waterfowl species (J. Nissen, pers. comm.). Trematodes have caused die-offs of several hundred waterbirds annually since 1996 on Shawno Lake and several thousand waterbirds annually since 2002 on the Mississippi River.

Recommended Management

Sites that currently provide high quality forage should be prioritized for protection and managed as important staging areas. Managers should minimize disturbances at these sites by instituting no-wake or non-motorized zones, fishing and hunting restrictions, and public awareness campaigns during spring and fall migration (Mowbray 2002; see Kenow et al. 2003). Annual changes in hunting regulations relative to changes in breeding population will continue to be adjusted to achieve appropriate harvest rates. In response to this species’ population decline, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently instituted a daily bag reduction for scaup within the Mississippi Flyway from three to two per day.

For sites with restoration and/or enhancement potential, managers should target wetlands that: (1) have large (>500m diameter) open-water zones; (2) are deep enough to support over-wintering population of amphipods; (3) allow management of fish populations; and (4) have surrounding lands that can be managed to reduce sedimentation (Anteau 2005). Because of the low food resources available at some historically important stopover sites, managing areas for aquatic invertebrates (e.g., amphipods) also may be necessary.

Research Needs

Biologists and agencies need to gather and improve information for managing Greater and Lesser Scaup separately: (1) distinguish the two species in surveys; (2) examine existing data to improve survey designs and data collection; and (3) obtain current survival, recovery, and harvest estimates (Austin et al. 2000). In order to better focus management efforts, more research is needed to identify factors limiting scaup populations. Researchers need to evaluate the spatial variation in food and habitat quality continentally to better understand how cumulative habitat changes affect scaup energetic or migration strategies (Austin et al. 2006). The effects of contaminants on reproduction, female body condition, and behavior also need study (Austin et al. 2000). To better refine scaup harvest management, more study is needed to: (1) evaluate sources of uncertainty in scaup harvest potential; (2) assess the value of using harvest age ratios to support harvest management decisions; (3) assess the precision and bias in scaup harvest data; and (4) assess the potential value of preseason banding, versus its cost, for harvest management (Austin et al. 2006).

Information Sources

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology species account: http://www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/BirdGuide/Lesser_Scaup.html

- Jahn L.R. and R.A. Hunt. 1964. Duck and coot ecology and management in Wisconsin. Technical Bulletin (33): 1-212. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison.

- North American Breeding Bird Survey: http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.htm

- Temple, S.A., J.R. Cary, and R. Rolley. 1997. Wisconsin Birds: A Seasonal and Geographic Guide. Wisconsin Society of Ornithology and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI.

- Upper Mississippi River Great Lakes Joint Venture Implementation Plan: http://www.fws.gov/midwest/NAWMP/documents/WaterfowlManagementPlan.pdf

- Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife Refuge aerial waterfowl survey results: http://www.fws.gov/midwest/UpperMississippiRiver/umrwf06.html

- Waterfowl Population Status report: http://www.fws.gov/migratorybirds/reports/status06/waterfowl%20status%202006.pdf

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). 1992. Upper Mississippi River and Great Lakes region joint venture – Wisconsin plan. Madison, WI.

References

- Anteau, M.J. 2002. Nutrient reserves of Lesser Scaup during spring migration in the Mississippi Flyway: a test of the spring condition hypothesis. M.Sc. thesis, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

- Anteau, M.J. and A.D. Afton. 2004. Nutrient reserves of Lesser Scaup (Aythya affinis) during spring migration in the Mississippi flyway: a test of the spring condition hypothesis. Auk 121(3): 917-929.

- Anteau, M.J. 2005. Ecology of Lesser Scaup and Amphipods in the Upper-Midwest: Scope and Mechanisms of the Spring Condition Hypothesis and Implications for Migration Habitat Conservation. Ph.D. dissertation, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

- Austin, J.E., C.M. Custer, and A.D. Afton. 1998. Lesser Scaup (Aythya affinis). In The Birds of North America, No. 338 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

- Austin, Jane E., Alan D. Afton, Michael G. Anderson, Robert G. Clark, Christine M. Custer, Jeffery S. Lawrence, J. Bruce Pollard, and James K. Ringelman. 1999. Declines of greater and lesser scaup populations: issues, hypotheses, and research directions. Summary Report for the Scaup Workshop. U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Jamestown, North Dakota. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Online. http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/1999/blubill/blubill.htm (Version 19MAR99).

- Austin, J.E., A.D. Afton, M.G. Anderson, R.G. Clark, C.M. Custer, J.S. Lawrence, J.B. Pollard, and J.K Ringelman. 2000. Declining scaup populations: issues, hypotheses, and research needs. Wildlife Society Bulletin 28(1): 254-263.

- Austin, J.E., M.J. Anteau, J.S. Barclay, G.S. Boomer, F.C. Rohwer, and S.M. Slattery. 2006. Declining Scaup Populations: Reassessment of the Issues, Hypotheses, and Research Directions. Consensus Report from the Second Scaup Workshop, 17–19 January 2006, Bismarck, ND

- Bellrose, F.C. 1976. Ducks, geese, and swans of North America. Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, PA.

- Cole, R.A. 2001. Exotic parasite causes large-scale mortality in American Coots. U.S. Geological Survey, National Wildlife Health Center, Madison, Wisconsin. National Wildlife Health Center Online. http://www.nwhc.usgs.gov (9 Feb. 2005).

- Custer, C.M. and T.W. Custer. 1996. Food habits of diving ducks in the Great Lakes after the zebra mussel invasion. J. Field Ornithol. 67(1): 86-89.

- Ehrlich, P.R., D.S. Dobkin, and D. Wheye. 1988. The birders handbook: a field guide to the natural history of North American birds. Simon & Schuster, Inc. New York.

- Jahn L.R. and R.A. Hunt. 1964. Duck and coot ecology and management in Wisconsin. Technical Bulletin (33): 1-212. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison.

- Kahl, R. 1991. Restoration of canvasback migrational staging habitat in Wisconsin: a research plan with implications for shallow lake management. Technical Bulletin (172): 1-47. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison.

- Kenow, K.P., C.E. Korschgen, J.M. Nissen, A. Elfessi, and R. Steinbach. 2003. A voluntary program to curtail boat disturbance to waterfowl during migration. Waterbirds 26(1): 77-87.

- Korschgen, C.E., L.S. George, and W. L. Green. 1985. Disturbance of diving ducks by boaters on a migrational staging area. Wildl. Soc. Bull. (13): 290-296.

- Mowbray, T.B. 2002. Canvasback (Aythya valisineria). In The Birds of North America, No. 659 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

- Petersen, L.R., M.A. Martin, J.M. Cole, J.R. March, and C.M. Pils. 1982. Evaluation of waterfowl production areas in Wisconsin. Technical Bulletin (135): 1-32. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison.

- Robbins, S.D., Jr. 1991. Wisconsin birdlife: Population and distribution past and present. Madison, WI: Univ. Wisconsin Press.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 2004. Waterfowl population status, 2004. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. U.S.A.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 2006. Waterfowl population status, 2006. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. U.S.A.

- Wheeler, W.E., R.C. Gatti, and G.A. Bartelt. 1984. Duck breeding ecology and harvest characteristics on Grand River Marsh wildlife area. Technical Bulletin (145): 1-49. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison.

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). 1992. Upper Mississippi River and Great Lakes region joint venture- Wisconsin plan. Madison, WI.

Contact Information

- Compiler: Steven C. Houdek, steve_houdek@usgs.gov

- Editor: Kim Kreitinger, K.Kreitinger@gmail.com