Photo by Dennis Malueg

Status/Protection

- Global Rank: G5 Key to global and state ranks

- State Rank: S4B

- WBCI Priority: SGCN, PIF, State Special Concern

Population Information

Federal BBS information can be obtained at http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html by clicking on Trend Estimates and selecting the species in question. All estimates are for 1966-2005.

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey: significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (WI): significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 23): non-significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 12): significant decline

- Chequamegon National Forest Bird Survey (NRRI): non-significant decline (1992-2005)

- WSO Checklist Project: Increasing frequency of reports (1983-2007)

Life History

- Breeding Range: Southern Yukon east across Canada and the northern U.S. (Briskie 1994).

- Breeding Habitat: Northern Hardwood, Aspen, Central Hardwood, Hemlock Hardwood, Red Pine, White Pine, Oak, Forested Ridge and Swale.

- Nest: Cup, woven from fine grasses and bark strips; located in lower to middle portion of canopy.

- Nesting Dates: Eggs: mid-May to mid-July.

- Foraging: Hover-glean, hawks.

- Migrant Status: Neotropical medium-range migrant.

- Habitat use during Migration: Not well known; likely variable.

- Arrival Dates: Late April to late May.

- Departure Dates: Adults probably depart July to Aug; young birds mid-August to early October.

- Winter Range: Southern Mexico to Panama, extreme south Florida.

- Winter Habitat: Forest edges, clearings, and second growth woodlands.

Habitat Selection

The Least Flycatcher is a forest generalist. It is found in almost every major type of deciduous and mixed forest, and less commonly in conifers. Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas results showed this species breeding in 17 major habitat types and 62 subtypes (Windels 2006). However, it is most commonly found in various stands of white oak, red oak, and sugar maple (Bond 1957, Mossman and Lange 1982). In the Baraboo Hills, the Least Flycatcher typically occupies stands where many small, pole-sized trees and tall saplings enter into a semi-open canopy of large oaks (Mossman and Lange 1982). In contrast, this species occurs more often under dense, closed canopies in northern Michigan (DellaSala and Rabe 1987). In northern hardwood forests of Wisconsin, it occurs in stands of all ages, but most predictably in pole-sized stands (Hoffman 1989, M. Mossman, pers. comm). It is encountered occasionally along forest edges and in small forest clearings created by creeks and roads (Mossman and Lange 1982, Briskie 1994). Less commonly, it is found in shrubby fields (Briskie 1994). This species is generally found in drier habitats than other forest Empidonax species (Walkinshaw 1966).

Least Flycatchers use a wide variety of tree species as nest sites, including maple, oak, birch, ash, and willow (Briskie 1994). Its neat, woven-grass nests usually are placed in a fork of a small tree or shrub, often against the main trunk. DellaSala and Rabe (1987) and Sherry (1979) found Least Flycatchers to nest in dense aggregations in northern Michigan, as did Mossman and Lange (1982) in Wisconsin. These aggregations adjust to forest disturbances, avoiding edges and clearings (DellaSala and Rabe 1987). One study in northern Wisconsin rarely found Least Flycatcher nests within 50 meters of forest edge (Flaspohler et al. 2001).

Habitat Availability

In the nineteenth century, the Least Flycatcher was found throughout the state. However, as mature deciduous cover declined in the southern half of the state, the species’ breeding range shifted northward (Robbins 1991). Today it breeds only in scattered locations in southern Wisconsin, including the Baraboo Hills (Mossman and Lange 1982, Anon 2002). The highest concentrations of Least Flycatchers now occur in the large tracts of deciduous and mixed forests in the northern half of the state (Robbins 1991, Sauer et al. 2005). Smith and Payne (1997) found that the Least Flycatcher was one of the two most common birds in low-lying areas of 28 to 45 year-old aspen stands in Wood County of central Wisconsin.

Population Concerns

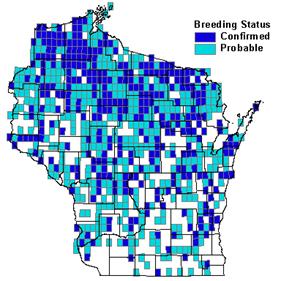

Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data suggest significant declines for this species in Wisconsin and range-wide (Sauer et al 2005). It remains a common breeder in northern Wisconsin. During the six-year period (1995-2000) of the Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas, observers documented probable or confirmed breeding status in 63% of surveyed quads (Windels 2006). Furthermore, breeding was confirmed in some of the southernmost counties of the state, contradicting previous studies that showed an absence of breeding Least Flycatchers in this region (Price et al. 1995).

An important factor in the decline of the Least Flycatcher is its sensitivity to forest fragmentation. DellaSala and Rabe (1987) found that disturbances creating forest openings caused aggregations of nesting Least Flycatchers to move deeper into the forest interior. In areas with extensive fragmentation where individual fragments lacked protected interiors, breeding aggregations were absent. Unlike many other forest interior species, Least Flycatcher nests are infrequently parasitized by Brown-headed Cowbirds. The reasons for the low parasitism rate are not well understood (Briskie 1994). The greatest causes of nest failure are predation, cold weather, and high winds (Darveau et al. 1993, Briskie 1994).

Recommended Management

Management and conservation of Least Flycatchers will require maintaining large, unfragmented deciduous forest tracts (WDNR 2005). Based on the work by DellaSala and Rabe (1987), the size and number of forest openings and breaks should be minimized. One large clearing is preferable to several clearings of intermediate size that fragment the forest (Briskie 1994). Habitat conservation in the Baraboo Hills, one of few areas in southern Wisconsin with a good population density (Mossman and Lange 1982), is recommended.

Conservation and management strategies for this species should be focused in the following Wisconsin ecological landscapes: Central Lake Michigan Coastal, Central Sand Plains, Forest Transition, North Central Forest, Northeast Sands, Northern Highland, Northern Lake Michigan Coastal, Northwest Lowlands, Northwest Sands, Southeast Glacial Plains, Superior Coastal Plain, and Western Coulee and Ridges (WDNR 2005).

Research Needs

Because of its recent declines, the status of the Least Flycatcher in Wisconsin should be monitored. In southern Wisconsin, breeding locations should be identified, closely monitored, and studied. The species responded well to mechanical thinning of young aspen stands in northern Minnesota (Christian 1996), which suggests a potential management tool. Finally, the social and mating behaviors of Least Flycatchers are poorly known and need study (Briskie 1994).

Information Sources

- Chequamegon National Forest Bird Survey (NRRI) species account: http://www.nrri.umn.edu/mnbirds/accounts/LEFLa2.htm

- Nicolet Northern Forest Bird survey map: http://www.uwgb.edu/birds/nnf/species/LEFL.htm

- North American Breeding Bird Survey: http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov

- Temple S.A., J.R. Cary, and R. Rolley. 1997. Wisconsin Birds: A Seasonal and Geographical Guide. Wisconsin Society of Ornithology and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI.

- Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas: http://www.uwgb.edu/birds/wbba/

References

- Anon. 2002. Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas: www.uwgb.edu/birds/wbba/

- Bond, R.R. 1957. Ecological distribution of breeding birds in the upland forest of southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 27(4): 351-384.

- Briskie, J.V. 1994. Least Flycatcher. The Birds of North America, No. 99 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

- Christian, D.P. 1996. Effects of mechanical strip thinning of aspen on small mammals and breeding birds in northern Minnesota, U.S.A. Can. J. For. Res. 26(7): 1284-1294.

- Darveau, M., G. Gauthier, and J. DesGranges. 1993. Nesting success, nest sites, and parental care of the Least Flycatcher, in declining maple forests. Can. J. Zool. 71: 1592-1601.

- DellaSala, D.A. and D.L. Rabe. 1987. Response of Least Flycatchers Empidonax minimus to forest disturbances. Biol. Cons. 41(4): 291-299.

- Flaspohler, D.J., S.A. Temple, and R. Rosenfield. 2001. Species-specific edge effects on nest success and breeding bird density in a forested landscape. Ecological Applications 11:32-46.

- Hoffman, R.M. 1989. Birds of Wisconsin northern mesic forests. Passenger Pigeon 51: 97-110.

- Mossman, M.J., and K.I. Lange. 1982. Breeding birds of the Baraboo Hills, Wisconsin: Their history, distribution and ecology. Wis. Dep. Nat. Resour. and Wis. Soc. Ornithol., Madison.

- Robbins, S.D., Jr. 1991. Wisconsin birdlife: Population and distribution past and present. Madison, WI: Univ. Wisconsin Press.

- Price, J., S. Droege, and A. Price. 1995. The Summer Atlas of North American Birds. Academic Press, New York, NY.

- Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, and J. Fallon. 2005. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2005. Version 6.2.2006. USGS Patuxent Wildlife ResearchCenter, Laurel, MD.

- Sherry, T.W. 1979. Competitive interactions and adaptive strategies of American Redstarts and Least Flycatchers in a northern hardwoods forest. Auk 96: 265-283.

- Smith, J.H., and N.F. Payne. 1997. Relationship of birds to various age aspen stands. Passenger Pigeon 59: 267-274.

- Walkinshaw, L.H. 1966. Summer observations of the Least Flycatcher in Michigan. Jack-pine Warbler 44: 150-168.

- Windels, S. 2006. Least Flycatcher. In Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Wisconsin. (N.J. Cutright, B.R. Harriman, and R.W. Howe, eds.) The Wisconsin Society for Ornithology, Inc. 602pp.

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). 2005. Wisconsin’s Strategy for Wildlife Species of Greatest Conservation Need. Madison, WI.

Contact Information

- Compiler: Tom Klubertanz, tklubert@uwc.edu

- Editors: Kim Kreitinger, K.Kreitinger@gmail.com | Mike Mossman, Michael.Mossman@Wisconsin.gov