Photo by Dennis Malueg

Status/Protection

- Global Rank: G4 Key to global and state ranks

- State Rank: S4B

- WBCI Priority: SGCN, PIF, State Special Concern

Population Information

Federal BBS information can be obtained at http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html by clicking on Trend Estimates and selecting the species in question. All estimates are for 1966-2005.

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey: significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (WI): non-significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 23): significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 12): non-significant decline

- Chequamegon National Forest Bird Survey (NRRI): non-significant decline (1992-2005)

- Nicolet National Forest Bird Survey (UWGB): significant decline (Howe and Roberts 2005)

- WSO Checklist Project: significant inverted u-shaped quadratic trend (1983-2007)

Life History

- Breeding Range: Southern Ontario south to Illinois east to the New England states (Confer 1992).

- Breeding Habitat: Shrub-carr, Alder Thicket, Open Bog-Muskeg, early successional forest (esp. aspen), successional fields and pastures, utility rights-of-way, beaver wetlands, young conifer plantations (in absence of herbicide application), hardwood swamps (e.g., black ash-dominated swamps), and mosaics (where two or more of these other habitat types meet) (Temple 2006, WDNR 2005, Golden-winged Warbler Atlas Project unpublished data).

- Nest: Cup, usually well-concealed on ground (Ehrlich et al. 1988).

- Nesting Dates: Eggs: late May to late June (Robbins 1991).

- Foraging: Foliage glean.

- Migrant Status: Neotropical migrant.

- Habitat use during Migration: Not well known.

- Arrival Dates: Early to late May (Robbins 1991).

- Departure Dates: Early August to mid-September (Robbins 1991).

- Winter Range: S. Central America to n. South America (Confer 1992)Winter Habitat: Woodland canopy, semi-open or less dense forests and forest borders or gaps (Confer 1992); montane oak forests, especially in Colombia, are suspected to be particularly important (ProAves unpublished data).

Habitat Selection

The Golden-winged Warbler occurs in a wide variety of early-successional habitats. In Wisconsin it often inhabits brushy clearcuts, shrubby swamps, overgrown abandoned agricultural fields, and edges of hardwood stands, especially aspen (Temple 2006). One to ten year-old aspen stands harbored a higher abundance of Golden-winged Warblers than other early seral habitats in north-central Wisconsin (Martin et al. in press). Golden-winged Warblers were present in high densities (0.55 males/ha) in young aspen clearcuts with high aspen sucker densities in Wisconsin (Roth and Lutz 2004) in contrast to clearcuts in the Appalachians and northeastern U.S. (Confer 1992, Klaus and Buehler 2001). In the national forests of Minnesota and Wisconsin, Golden-winged Warbler presence was best predicted by the amount of lowland shrub cover within a 100 meter buffer area of the survey point (Hanowski 2002).

In the Appalachians and northeastern U.S., common elements of Golden-winged Warbler habitat include a clumped distribution of herbs and shrubs (Confer 1992), an extensive and diverse edge (Rossell et al. 2003), and a high herbaceous cover (Klaus and Buehler 2001, Confer et al. 2003). The Golden-winged Warbler selects areas based on their degree of patchiness and structural complexity (Rossell et al. 2003). Payne (1991) suggested that Golden-winged Warblers tend to occur in more open habitats than Blue-winged Warblers in Michigan, often occurring in earlier stages of plant succession. Also, where Golden-winged Warblers co-occur with Blue-winged Warblers, Golden-winged Warblers may predominate in wetter shrub habitats (Will 1986). Nest sites are located along the edge of a forest field or in small forest openings. Nests are placed on the ground, often at the base of goldenrod, berry bushes or some other leafy plant material (Confer 1992).

Habitat Availability

Historically, the Golden-winged Warbler had a broad distribution across the state (Robbins 1991). Extensive clearcutting during the nineteenth century created ample suitable habitat for this early-successional habitat specialist (Temple 2006). More recently, the Golden-winged Warbler’s breeding range has contracted northward and it is now largely extirpated from most historical breeding areas in the southern regions of the state. Loss of shrubby habitat to succession and development may play a role in this range shift, along with global climate change and genetic introgression with the northward-expanding Blue-winged Warbler.

Alder thickets remain common and widespread in northern and central Wisconsin, but also occur at isolated locales in the southern part of the state. Shrub-carr remains common and widespread in southern Wisconsin, but also occurs in the north (WDNR 2005). However, these lowland shrub habitats are increasingly threatened by human development especially along riparian zones. Though aspen cover remains stable in the northern third of Wisconsin, forest inventories documented decreases in aspen cover by 36% and 17% for the central and southern thirds of the state respectively between 1983 and 1996 (Schmidt 1997). However, a statewide increase in the seedling/sapling age-class of aspen forest was also observed over the same period suggesting increased habitat availability in some areas for Golden-winged Warblers. It is unknown if this represents quality breeding habitat.

Population Concerns

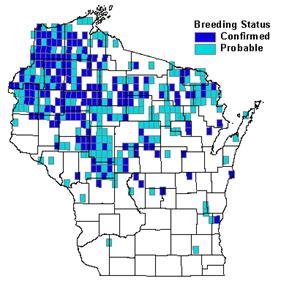

Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data indicate population declines range-wide and in Wisconsin (-1.8%/yr), although the latter trend has marginal statistical significance (P=0.08) (Sauer et al. 2005). In Wisconsin it is a fairly common summer resident north and central, but rare in the south (Robbins 1991). During the six-year period (1995-2000) of the Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas, observers recorded breeding activity in 39% and confirmed nesting in 15% of the surveyed quads, primarily in the northern half of the state (Temple 2006). Succession of early seral woodlands and hybridization with the northward expanding Blue-winged Warbler are major concerns in Wisconsin (WDNR 2005) and throughout this species’ breeding range. Even where suitable habitat remains, hybridization may contribute to local extirpations of Golden-winged Warblers (Confer et al. 2003). Brown-headed Cowbird parasitism may be an additional negative factor leading to the Golden-winged Warbler decline (Confer et al. 2003) though this may be less of a concern in northern landscapes with extensive forest cover and low cowbird populations.

Recommended Management

There are important opportunities for Golden-winged Warbler conservation and management in Northern Wisconsin and Minnesota because of high population densities and the absence of Blue-winged Warblers outside of a few individuals (Martin et al. in press). Management efforts should focus on maintaining a mosaic of lowland and Grassland-shrub communities, especially alder thicket, shrub-carr, and young aspen stands (WDNR 2005). Roth and Lutz (2004), Martin et al. (in press), and Hanowski (2002) found high Golden-winged Warbler use in aspen stands up to 10-11 years post-harvest in Wisconsin and Minnesota. Golden-winged Warblers continue to use older stands at lower densities, selecting open areas created by poor aspen regeneration, wet pockets, old landings, and utility and road rights-of-way (Hanowski 2002, Roth and Lutz 2004). Roth and Lutz (2004) recommended a 40-year rotation of several adjacent aspen stands such that one stand in an area always provides suitable breeding habitat. This type of management may be best applied in areas of known breeding activity to maintain or increase local populations.

Protection and restoration of lowland shrub communities also is a necessary measure toward maintaining Golden-winged Warbler populations. Shearing and burning of wetland shrub habitats is not recommended; in Minnesota these activities led to significantly fewer individuals compared to unmanaged sites within the first three years following management activities (Hanowski et al. 1999). The amount of time needed for these managed wetland shrub habitats to become attractive to Golden-winged Warblers is unknown.

Conservation and management strategies for this species should be focused in the following Wisconsin ecological landscapes: Central Sand Plains, Central Lake Michigan Plain (primarily Navarino Wildlife Area), Forest Transition, Northcentral Forest, Northeast Sands, Northern Highland, Northern Lake Michigan Coastal, Northwest Lowlands, Northwest Sands, and Superior Coastal Plain (especially Bibon Swamp on the White River) (WDNR 2005).

Research Needs

More research is needed into the limiting factors contributing to this species’ decline including loss of habitat, low productivity or survival, hybridization with Blue-winged Warblers, and migration hazards. Potentially confounding effects of climate change on these factors should be examined (Price 2004). In August 2005, the Golden-winged Warbler Working Group identified the following top research priorities range-wide: 1) define quality habitat; 2) develop a genetic and stable isotope atlas; 3) expand population monitoring; and 4) develop a standardized habitat classification system (Buehler et al. in press). In Wisconsin, more information is needed on preferred site-level characteristics, including clearcut size and placement within a landscape context, stem density requirements, and the efficacy of log-landings.

Information Sources

- Audubon Watch List: http://audubon2.org/webapp/watchlist/viewSpecies.jsp?id=87

- Chequamegon National Forest Bird Survey (NRRI) species account: http://www.nrri.umn.edu/mnbirds/accounts/GWWAa2.htm

- Golden-winged Warbler Atlas Project: http://www.birds.cornell.edu/gowap/

- Nicolet National Forest Bird Survey Map: http://www.uwgb.edu/birds/nnf/species/GWWA.htm

- North American Breeding Bird Survey: http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html

- Temple S.A., J.R. Cary, and R. Rolley. 1997. Wisconsin Birds: A Seasonal and Geographical Guide. Wisconsin Society of Ornithology and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI.

- Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas: http://www.uwgb.edu/birds/wbba/

References

- Buehler, D.A. A.M. Roth, R. Vallender, T.C. Will, J.L. Confer, R.A. Canterbury, S. Barker Swarthout, K.V. Rosenberg, and L.P. Bulluck. 2007. Status and conservation of golden-winged warblers (Vermivora chrysoptera) in North America. The Auk 124(4):1439-1445.

- Confer, J.L., J.L. Larkin, and P.E. Allen. 2003. Effects of vegetation, interspecific competition, and brood parasitism on golden-winged warbler (Vermivora chrysoptera) nesting success. Auk 120(1): 138-144.

- Confer, J.L. 1992. Golden-winged Warbler. In The Birds of North America, No. 20 (A. Poole, P. Stettenheim, and F. Gill, Eds.). Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, DC: The American Ornithologists’ Union.

- Ehrlich, P.R., D.S. Dobkin, and D. Wheye. 1988. The birders handbook: a field guide to the natural history of North American birds. Simon & Schuster, Inc. New York.

- Hanowski, J. 2002. Habitats and landscapes used by breeding golden-winged warblers in western Great Lakes forests. The Loon 74: 127-133.

- Hanowski, J.M., D.P. Christian, and M.C. Nelson. 1999. Response of breeding birds to shearing and burning in wetland brush ecosystems. Wetlands 19: 584-593.

- Howe, R.W. and L.J. Roberts. 2005. Sixteen years of habitat-based bird monitoring in the Nicolet National Forest. In C.J. Ralph and T.D. Rich, editors. Bird Conservation Implementation and Integration in the Americas: Proceedings of the Third International Partners in Flight Conference. 2002 March 20-24; Asilomar, California, Volume 2. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-191. Albany, CA: Pacific Southwest Research Station, Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; 643 p.

- Klaus, N.A. and D.A. Buehler. 2001. Golden-winged Warbler breeding habitat characteristics and nest success in clearcuts in the southern Appalachian Mountains. Wilson Bulletin 113(3): 297-301.

- Martin, K.J., S. Lutz, and M. Worland. In press. Golden-winged Warbler habitat use and abundance in northern Wisconsin. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology.

- Payne, R.B. 1991. Golden-winged Warbler. In The Atlas of Breeding Birds of Michigan (R.Brewer, G.A. McPeek, and R.J. Adams, Jr., eds.). Michigan State University Press: East Lansing, MI.

- Price, J. 2004. Climate change and Wisconsin’s nongame birds. Passenger Pigeon 66:51-59.

- Robbins, S.D., Jr. 1991. Wisconsin birdlife: Population and distribution past and present. Madison, WI: Univ. Wisconsin Press.

- Rossell, C.R., S.C. Patch, and S.P. Wilds. 2003. Attributes of golden-winged warbler territories in a mountain wetland. Wildlife Society Bulletin 31(4): 1099-1104.

- Roth, A.M. and S. Lutz. 2004. Relationship between territorial male golden-winged warblers in managed aspen stands in northern Wisconsin, USA. Forest Science 50: 153-161.

- Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, and J. Fallon. 2005. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2005. Version 6.2.2006. USGS Patuxent Wildlife ResearchCenter, Laurel, MD.

- Schmidt, T.L. 1997. Wisconsin forest statitics, 1996. USDA Forest Service North Central Experimental Station Research Bulletin. NC-183. 457p.

- Temple, S.A. 2006. Golden-winged Warbler. In Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Wisconsin. (N.J. Cutright, B.R. Harriman, and R.W. Howe, eds.) The Wisconsin Society for Ornithology, Inc. 602pp.

- Will, T.C. 1986. The behavioral ecology of species replacement: blue-winged and golden-winged warblers in Michigan. PhD dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. 126p.

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). 2005. Wisconsin’s Strategy for Wildlife Species of Greatest Conservation Need. Madison, WI.

Contact Information

- Compiler: Kim Kreitinger, K.Kreitinger@gmail.com

- Editor: Amber Roth, amroth@mtu.edu