Photo by Scott Franke

Status/Protection

- Global Rank: G5 Key to global and state ranks

- State Rank: S1B, S2N

- WBCI Priority: SGCN, WBIRD, State Endangered

Population Information

The Federal BBS information can be obtained at http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html by clicking on Trend Estimates and selecting the species in question. All estimates are for time period (1966-2005).

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey: significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (WI): N/A

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 23): N/A

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 12): N/A

- WSO Checklist Project: significant decrease (1983-2007)

Life History

- Breeding Range: Rocky Mountains in Alberta and Montana east to Newfoundland, south along the Atlantic Coast and Gulf of Mexico; sporadically along the Great Lakes states and provinces (Nisbet 2002).

- Breeding Habitat: Emergent Marsh, Great Lakes Beach and Dune; islands with rocky or sandy substrate.

- Nest: Scrape on ground in open area with loose substrate (Nisbet 2002).

- Nesting Dates: Eggs: late May to early August (Robbins 1991).

- Foraging: High dives (Ehrlich et al. 1988).

- Migrant Status: Short-distance migrant, Neotropical migrant.

- Habitat use during Migration: Great Lakes Open Water, Great Lakes Beach and Dune.

- Arrival Dates: Mid-April to mid-June (Robbins 1991).

- Departure Dates: Early August to mid-October (Robbins 1991).

- Winter Range: Caribbean and South America.

- Winter Habitat: Little information; beaches, mudflats across continental shelf.

Habitat Selection

The Common Tern typically nests on coastal islands, barrier beaches, promontories attached to mainland, and salt and fresh water marshes along the coast, and small treeless, rocky or gravely islands in interior lakes of North America. Because nest sites are susceptible to flooding, the Common Tern often locates its nest at the highest point of an island or shoreline, usually elevated 0-5 m above water level (Nisbet 2002). Nesting substrates include gravel, bare ground, sand, shell, cobble, and floating cattail islands and frequently human-modified substrates such as dredge spoil islands, chipped concrete, riprap, and dismantled piers (e.g., Ashland Pier in Chequamegon Bay) (Harris and Matteson 1975, Matteson 1988, Nisbet 2002, Matteson 2006). Throughout its range, the Common Tern nests in areas of sparse (10-30%) vegetation cover and may abandon nests if cover exceeds 30% (Burger and Gochfeld 1991). However, Cook-Haley and Millenbah (2002) found Common Terns in the northern Great Lakes to have higher nesting success in areas with moderate (40-50%) vegetation cover, which suggests more study is needed on the relationship between vegetation cover and survivorship.

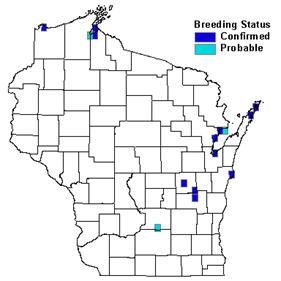

The Common Tern nests in colonies ranging from tens to thousands of pairs and rarely nests solitarily (Burger and Gochfield 1991). Colonies can be monospecific or mixed with other tern species and generally show high site tenacity. Common Tern pairs frequently nest within a few feet of formerly occupied sites if conditions remain suitable (Austin 1949). In Wisconsin, they return each spring to a handful of small island colonies on Lake Superior and Lake Michigan (Harris and Matteson 1975, Matteson 1988) and Winnebago Pool Lakes in Wisconsin (Mossman et al. 1988, Matteson 2003). Common Terns nesting in the Great Lakes and Midwest migrate east to join terns from the Atlantic Coast for the flight to the Central and South American wintering grounds (Austin 1953, Haymes and Blokpoel 1978, Blokpoel et al. 1987). Migration habitats in Wisconsin consist of lake shorelines, bays, and rivers primarily in eastern and northeastern Wisconsin and occasionally along the Mississippi River (Matteson 1988).

Habitat Availability

Historically, the Common Tern was a common migrant along Lake Michigan and frequently nested on Lake Michigan islands in northeastern Wisconsin (Matteson 1988). It also has nested intermittently in southeastern Wisconsin (Winnebago Pool, Koshkonong, Elkhart, Mason, Kegona lakes), along Lake Superior (Barker’s Island, Chequamegon Bay, Duluth-Superior Harbor), and other northern Wisconsin lakes and wetlands (Kumlien and Hollister 1903, Harris and Matteson 1975, Matteson 1988, Mossman et al. 1988). Currently, known Common Tern colony sites are located in Duluth-Superior harbor, Chequamegon Bay, Green Bay, and Winnebago Pool Lakes. Breeding habitat used by this species often is unstable and subject to flooding, erosion, vegetative encroachment, and other natural and anthropogenic disturbances. Given these unpredictable conditions, the availability of suitable nesting habitat fluctuates from year to year.

Population Concerns

The Common Tern experienced dramatic population declines range-wide in the late nineteenth century primarily attributed to the millinery trade. Coincident with protection efforts in the early twentieth century, Common Tern populations began to recover, peaked in the 1930s, and have subsequently fluctuated regionally (Nisbet 2002). Wisconsin’s Common Tern population declined significantly between the early 1950s and early 1970s and was listed as state endangered in 1979. From 1979-1987 the state population increased by more than 300% (Matteson 1988) but has since experienced another decline. Matteson (1988) presented a recovery goal of 1,000 nesting pairs at seven or more colony sites by the year 2000; however, only two colonies have been relatively stable and productive in the past two decades (Matteson 2006). Factors contributing to the decline are: (1) competition with Ring-billed Gulls for nesting sites; (2) vegetative succession at colony sites; (3) high water levels and erosion; (4) human disturbance at colony sites; (5) nest predation; and (6) organochloride contaminants (Harris and Matteson 1975, Scharf 1981, Shugart and Scharf 1983, Matteson 1988, Nisbet 2002).

Recommended Management

Partnerships between state and federal agencies and private organizations dedicated to the restoration, conservation, and management of Great Lakes coastal ecosystems will benefit the long-term management of both Caspian and Common Terns (WDNR 2005). Matteson (1988) proposed four geographical management units in Wisconsin: Duluth-Superior Harbor, Chequamegon Bay, Green Bay, and Winnebago Pool Lakes. Intensive management within these units should: (1) maintain a desirable mix of open substrate with scattered vegetation cover (i.e., prevent succession); (2) determine and implement measures to control nesting Ring-billed Gulls and Herring Gulls at tern colony sites; (3) determine and implement measures to control predators at colony sites; (4) minimize or prevent human disturbance to colonies; (5) reduce or eliminate the discharge of organochloride and mercury; (6) create and maintain existing artificial nesting sites (e.g., dredge spoil islands, derelict piers); and (7) develop and implement education programs to engage local communities in Common Tern conservation (Morris 1980, Scharf 1981, Matteson 1988, Nesbit 2002).

Research Needs

Annual monitoring of statewide nesting populations, recruitment, production, and factors affecting colony stability is needed. Additional study of the relationship between vegetation cover and survivorship would further management efforts. Researchers should continue to monitor and assess the effects of chemical contamination on Common Tern reproduction and survival. More direct comparison studies are needed on the ecology and physiology of fresh and salt water breeding colonies, including the transition of fresh water birds to marine foraging in winter. More information on the foraging ecology, energetics, molt, and limiting factors on the wintering grounds also is warranted.

Information Sources

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology species account: http://www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/BirdGuide/Common_Tern.html

- North American Breeding Bird Survey: http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html

- Tern colony site management techniques: http://www.waterbirdconservation.org/plan/rpt-sitemanagement.pdf

- Waterbird Conservation for the Americas: http://www.waterbirdconservation.org/pubs/ContinentalPlan.cfm

- Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas: http://www.uwgb.edu/birds/wbba/

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources fact sheet: http://www.dnr.state.wi.us/org/land/er/factsheets/birds/Comtern.htm

References

- Austin, O.L. 1953. The migration of the common tern (Sterna hirundo) in western hemisphere. Bird-Banding 24:39-55.

- Blokpoel, H., G.D. Tessier, and A. Harfenist. 1987. Distribution during post-breeding dispersal, migration, and overwintering of common terns color-marked on the lower Great Lakes. Journal of Field Ornithology 58:206-217.

- Burger, J. and M. Gochfield. 1991. The Common tern, its breeding biology and social behavior. Columbia University Press, New York.

- Cook-Haley, B.S. and K.F. Millenbah. 2002. Impacts of vegetative manipulations on Common Tern nest success at Lime Island, Michigan. Journal of Field Ornithology 73(2): 174-179.

- Ehrlich, P.R., D.S. Dobkin, and D. Wheye. 1988. The birders handbook: a field guide to the natural history of North American birds. Simon & Schuster, Inc. New York.

- Harrison, J.T., and S.W. Matteson. 1975. Gulls and terns as indicators of man’s impact upon Lake Superior. University of Wisconsin Sea Grant College Program Technical Report 227. Unversity of Wisconsin-Madison. 45pp.

- Haymes, G.T. and H. Blokpoel. 1978. Seasonal distribution and site tenacity of the Great Lakes common tern. Bird-Banding 49:142-151.

- Kumlien L. and N. Hollister. 1903. The birds of Wisconsin. Bulletin of the Wisconsin Hatural History Society 3 1-143; reprinted with A.W. Schorger’s revisions, Wisconsin Society for Ornithology. 1951.

- Matteson, S.W. 1988. Wisconsin common tern recovery plan. Wisconsin Endangered Resources Report 41. Bureau of Endangered Resources, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison. 52 pp.

- Matteson, S.W. 2003. Conservation of endangered, threatened and nongame bird. Performance Report, 1 July 2002-30 June 2003. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison. 35pp.

- Matteson, S.W. 2006. Common Tern. In Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Wisconsin (N.J. Cutright, B.R Harriman, and R.W Howe, eds.). Wisconsin Society of Ornithology, Inc. 602pp.

- Morris, R.D., I.R. Kirkham, and J.W. Chardine. 1980. Management of a declining common tern colony. Journal of Wildlife Management 44:241-245.

- Mossman, M.J., A.F. Techlow III, T.J.Ziebell, S.W. Matteson, and K.J. Fruth. 1988. Nesting gulls and terns of Winnebago Pool and Rush Lake, Wisconsin. Passenger Pigeon 50:107-117.

- Nisbet, I.C.T. 2002. Common Tern (Sterna hirundo). In A. Poole and F. Gill, eds. The birds of North America, No 618. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, and the American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington D.C.

- Robbins, S.D. 1991. Wisconsin birdlife: population & distribution, past & present. Univ of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI.

- Rolley, R. 2005. Wisconsin Checklist Project. http://dnr.wi.gov/org/land/wildlife/harvest/reports/07checklist.pdf (6 April 2007)

- Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, and J. Fallon. 2005. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2005. Version 6.2.2006. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD.

- Scharf, W.C. 1980. The significance of deteriorating man-made islands habitats to common terns and ring-billed gulls in the St. Mary’s River, Michigan. Colonial Waterbirds 4:155-159.

- Shugart, G.W. and W.C. Scharf. 1983. Common terns in the northern Great Lakes: current status and population trends. Journal of Field Ornithology 54:160-169.

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). 2005. Wisconsin’s Strategy for Wildlife Species of Greatest Conservation Need. Madison, WI.

Contact Information

- Compiler: Dan Haskell, danhaskell@hotmail.com

- Editor: Kim Kreitinger, K.Kreitinger@gmail.com