Photo by Ohio Dept. of Natural Resources

Status/Protection

- Global Rank: G5 Key to global and state ranks

- State Rank: S1B

- WBCI Priority: SGCN, State Endangered

Population Information

Federal BBS information can be obtained at http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html by clicking on Trend Estimates and selecting the species in question. All estimates are for 1966-2005.

*Note: There are important deficiencies with these data. These results may be compromised by small sample size, low relative abundance on survey route, imprecise trends, and/or missing data. Caution should be used when evaluating this trend.

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey: non-significant decline*

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (WI): N/A

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 23): N/A

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 12): N/A

- WSO Checklist Project: N/A (not numerous enough to be measured by the Checklist Project)

Life History

- Breeding Range: Throughout most of the U.S., but rare and local in many states; south through Central and South America (Marti 1992).

- Breeding Habitat: Idle Cool-season Grasses, Idle Warm-season Grasses, Wet Prairie, Wet-mesic Prairie, Southern Sedge Meadow and Marsh, Pasture, Hay.

- Nest: Cavity in tree, abandoned building, barn, church steeple, rock crevice, nest box created specifically for this species (Ehrlich et al. 1988, Marti 1992).

- Nesting Dates: EGGS: mid-April to mid-August (Robbins 1991).

- Foraging: Low patrol (usually in flight ~1.5-4.5 m above ground), swoops, and occasionally hunts from a perch (Ehrlich et al. 1988, Marti 1992).

- Migrant Status: Permanent resident and short-distance migrant.

- Habitat use during Migration: Usually same as breeding habitat.

- Arrival Dates: Not well known; probably mid-March to late April (Robbins 1991).

- Departure Dates: Not well known; probably October to November (Robbins 1991).

- Winter Range: Same as breeding range, except northernmost populations undergo partial migration (Marti 1992). Wisconsin birds have been found in the state during winter; in some years mortality results from deep snow and cold temps (BER 1997).

- Winter Habitat: Same as breeding habitat.

Habitat Selection

The Barn Owl inhabits open rural lands or grasslands exhibiting topographical relief with some combination of wet meadow, wetland edge, pasture, oldfield, grain crop, hayfield, hedges, and fencerows, usually within 1-2 km of permanent water and adjacent to woodlot edge (Matteson and Petersen 1988). The quantity and quality of dense grass habitats are significantly correlated with Barn Owl nest activity (Colvin and Hegdal 1988). The Barn Owl is a cavity-nesting bird which uses natural as well as human-created cavities. Barn Owl nest sites in Wisconsin include concrete-domed silos, barns, tree cavities, abandoned farm buildings, church steeples, or possibly a hole in a bank or cliff (Matteson and Petersen 1988). Additionally, Barn Owls will readily use nest boxes. Colvin and Hegdal (1986) noted that the annual proportion of nests found in nest boxes was similar to that observed for tree cavities prior to box installation. Vole (Microtus sp.) density is also associated with habitat quality for this species. One year of poor meadow vole abundance can result in a rapid population decline while one year of substantial meadow vole abundance can result in rapid population recovery (B. Colvin pers. comm. in Schneider and Pence 1992). This species is not found in densely-forested regions (Marti 1992).

Habitat Availability

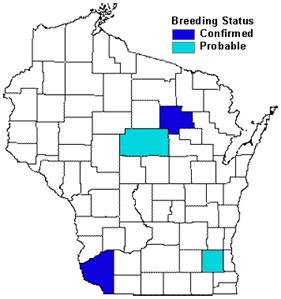

In Wisconsin the Barn Owl is primarily found in the southern and southeastern portions of the state. Seldom has the species nested north of an east-west line along the northern border of Dodge County (Matteson and Petersen 1988). In these areas, grasslands large enough to attract Barn Owls are rare and subject to fragmentation, especially on private agricultural lands (Sample and Mossman 1997). The conversion of pasture and fallow fields to row crops has lowered the amount of quality habitat available in Ohio (Colvin 1985) and probably throughout the Midwest.

Population Concerns

A marked decline in sightings during the last half of the twentieth century led Barn Owls to be listed as a state endangered species (BER 1997). During the six-year period of the Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas (1995-2000), observers reported only three confirmed Barn Owl breeding records (Matteson 2006). However, the Barn Owl has likely always been present at low densities in Wisconsin (Robbins 1991). Wisconsin lies at the northern limit of the Barn Owl’s breeding range (Hamerstrom 1972, Karalus and Eckert 1974). It may be that Wisconsin winters historically have limited the number of Barn Owls that inhabit the southern portions of the state, and when combined with habitat loss, may have made the species very rare (Matteson and Petersen 1988).

Standard avian monitoring techniques do not adequately estimate population trends for this species. Though data from Wisconsin and surrounding states suggest population declines, long-term, systematic monitoring is required before Barn Owl population trends are truly understood (Matteson and Petersen 1988, Schneider and Pence 1992).

Recommended Management

Wisconsin initiated a Barn Owl captive breeding program in the spring of 1980 to “reestablish a breeding population of Barn Owls based on captive-reared stock in southeast Wisconsin.” From 1982-1987, 86 captive-bred Barn Owl young were released or escaped in southeastern Wisconsin. The Bureau of Endangered Resources decided in 1987 to discontinue the captive-breeding program since there was no evidence that it had enhanced the state’s Barn Owl population (Matteson and Petersen 1988). Captive release programs in other midwestern states have produced similar results (Schneider and Pence 1992).

Barn Owl population declines in Wisconsin and elsewhere in the Midwest are likely attributed to habitat loss and consequent inadequate food supply and nesting sites (Matteson and Petersen 1988). Management efforts should encourage agencies and land holders to preserve existing grasslands and acquire additional land, such as cropland, which can then be converted to grassland. Such efforts will benefit not only the Barn Owl population, but other obligate grassland bird species of Wisconsin. Additionally, nest box provisions near areas of quality foraging habitat may be another important management strategy (Matteson and Petersen 1988, Schneider and Pence 1992). Conservation and management strategies for this species should be focused in the following Wisconsin ecological landscapes: Central Sand Plains, Southeast Glacial Plains, Southwest Savanna, Western Coulee and Ridges, and Western Prairie (WDNR 2005).

Research Needs

Relatively little is known about the precise habitat characteristics (e.g., quantity and quality of grass habitats) needed to support a productive Barn Owl nesting pair (Schneider and Pence 1992). A quality habitat assessment index should incorporate features such as mean reproductive success, nesting habitat characteristics, and analyses of owl pellet contents (Matteson and Petersen 1988). Research also is needed to evaluate the effects of existing land use practices and potential management practices on important prey species (Schneider and Pence 1992).

Information Sources

- Bird Studies Canada - Barn Owl Nest Box Plans: http://www.bsc-eoc.org/regional/barnowlbox.html

- Bird Studies Canada - Barn Owl Recovery Plan: http://www.bsc-eoc.org/regional/barnowl.html

- Managing Habitat for Grassland Birds: A Plan for Wisconsin: http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/birds/wiscbird/

- North American Breeding Bird Survey: http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov

- Wisconsin DNR Barn Owl web page: http://www.dnr.state.wi.us/org/land/er/factsheets/birds/barnowl.htm

- Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas: http://www.uwgb.edu/birds/wbba/

- Sumner Matteson, Avian Ecologist, Wisconsin DNR 608-266-1571

References

- Bureau of Endangered Resources. 1997. The endangered and threatened vertebrate species of Wisconsin. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Bureau of Endangered Resources. Madison, WI. Publ. No. ER-091.

- Colvin, B.A. 1985. Common Barn Owl population decline in Ohio and the relationship to agricultural trends. Journal of Field Ornithology 56 (3): 224-235.

- Colvin, B.A. and P.L. Hegdal. 1986. Comments on barn owl nest boxes. U.S. Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Wildl, Res. Center, unpubl. rep., Denver. 6pp.

- Colvin, B.A. and P.L. Hegdal. 1988. Summary of 1988 field activities. U.S. Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Wildl. Res. Center, unpubl. rep., Denver. 8pp.

- Erlich, P., D. Dobkin, and D. Wheye. 1988. The Birder’s Handbook: A Field Guide to the Natural History of North American Birds. Simon and Schuster, New York, NY.

- Hamerstrom, F. 1972. Birds of prey of Wisconsin. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 64pp.

- Karalus, K.E. and A.W. Eckert. 1974. The Owls of North America (north of Mexico). Doubleday and Co., Inc., Garden City, N.Y. 278pp.

- Marti, C.D. 1988. The Common Barn Owl, pp. 535–550 in Audubon Wildlife Report 1988/1989 (W. J. Chandler, Ed.). Academic Press, San Diego.

- Marti, C.D. 1992. Barn Owl. In The Birds of North America, No. 1 (A. Poole, P. Stettenheim, and F. Gill, Eds.). Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, DC: The American Ornithologists’ Union.

- Matteson, S.W. 2006. Barn Owl. In Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Wisconsin. (N.J. Cutright, B.R. Harriman, and R.W. Howe, eds.) The Wisconsin Society for Ornithology, Inc. 602pp.

- Matteson, S.W. and L. Petersen. 1988. Wisconsin Common Barn Owl Management Plan. Endangered Resources Rep.#37. WI Department of Natural Resources, Bureau of Endangered Resources. Madison, WI.

- Robbins, S. D. 1991. Wisconsin birdlife: population & distribution, past & present. Univ. of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI.

- Sample, D.W., and M. J. Mossman. 1997. Managing habitat for grassland birds - a guide for Wisconsin. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI. PUBL-SS-925-97.

- Schneider, K.J. and D.M. Pence, eds. 1992. Migratory nongame birds of management concern in the Northeast. U.S. Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Newton Corner, Massachusetts. 400pp.

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). 2005. Wisconsin’s Strategy for Wildlife Species of Greatest Conservation Need. Madison, WI.

Contact Information

- Compiler: William P. Mueller, iltlawas@earthlink.net

- Editor: Kim Kreitinger, K.Kreitinger@gmail.com