Photo by Dennis Malueg

Status/Protection

- Global Rank: G4 Key to global and state ranks

- State Rank: S4B, S2N

- WBCI Priority: SGCN, State Special Concern

Population Information

The Federal BBS information can be obtained at http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html by clicking on Trend Estimates and selecting the species in question. All estimates are for time period (1966-2005).

*Note: There are important deficiencies with these data. These results may be compromised by small sample size, low relative abundance on survey route, imprecise trends, and/or missing data. Caution should be used when evaluating this trend.

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey: significant increase

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (WI): significant increase*

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 23): significant increase*

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 12): significant increase*

- WSO Checklist Project: Increasing (1983-2007)

WDNR maintains a 31-year breeding population census.

Life History

- Breeding Range: Alaska south to California and east across Canada and the Great Lakes states to the Atlantic Coast; local breeding populations along the Gulf Coast (Buehler 2000).

- Breeding Habitat: Inland Open Water, Forested Ridge and Swale, Bottomland Hardwood; forested areas adjacent to large bodies of water.

- Nest: Platform.

- Nesting Dates: February 15 (southern Wisconsin) and March 15 (northern Wisconsin).

- Foraging: High patrol (secondary low patrol swoops).

- Migrant Status: Permanent Resident (most adults) and short-distance migrant (most immatures).

- Habitat use during Migration: Similar to winter habitat; Great Lakes open water.

- Arrival Dates: February (Adults) and March (immature).

- Departure Dates: October and November, but may over winter.

- Winter Range: Primarily in temperate zone below 500m with open water.

- Winter Habitat: Associated with some open water with protection from inclement weather.

Habitat Selection

Commonly breeds in forested areas adjacent to large bodies of water (Buehler 2000). Bald Eagles prefer forest stands that are mature or old growth with many tall, supercanopy trees (Stalmaster 1987). Bald Eagles have a propensity to build their nests near water. Actual distance to water varies within and among populations (Buehler 2000). In Alaska, 99% of nests are within 200 m of water the average only 40 m from the shoreline (Stalmaster 1987). However, Bald Eagles in Florida nested within 3 km of bodies water (McEwan and Hirth 1979), 1.2 km in Minnesota (Fraser et al. 1985) and 7.2 km in Oregon (Anthony and Isaacs 1989). This may be due to the lack of suitable trees along the shoreline or human disturbance (Fraser et al. 1985, Anthony and Isaacs 1989, Wood et al. 1989). Eagles select nest trees on the basis of appearance and form and they use coniferous trees more often than deciduous trees (Bent 1961, Stalmaster 1987). In northern Wisconsin, Bald Eagles selected large, supercanopy white pines (Pinus strobus) or red pines (Pinus resinosa). Eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides) trees where selected along the lower Wisconsin and Mississippi rivers (WBBA unpubl. data). Generally, the nest tree is one the tallest with accessible limbs capable of holding large stick built nest, provide open flight to and from nest, and have a panoramic view of the surrounding terrain (McEwan and Hirth 1979, Andrew and Mosher 1982, Stalmaster 1987, Anthony and Isaacs 1989, Wood et al. 1989, Livingston et al. 1990). The nest is usually placed in top quarter of tree, just below the crown and against the trunk or in a fork of large branches closed to trunk (Buehler 2000). Gostomski and Matteson (1999) reported a pair of Bald Eagles using a former Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) nest in the Apostle Islands. Nests are often reused year after year.

The presence of large open areas where prey can be killed and eaten is a key element of foraging habitat (Stalmaster 1987). This includes lakes and rivers including their shorelines, beaches, gravel, sand and mud bars and associated physiographic characteristics (Stalmaster 1987). Nesting, perching and roosting trees and a minimal amount of human disturbance in the area will heighten the suitability of the foraging habitat (Stalmaster 1987). Buehler (2000) describes good foraging habitat by conditions that make live fish available or conditions that fish, birds, and mammals is available as carrion. Bald eagles may prefer shallow warm water lakes or in less turbulent river pools, which supports a higher diversity (species richness) of benthic-feeding and shallow dwelling fish (Livingston et al. 1990). Bald Eagles’ nest are generally within optimal foraging habitat (Andrew and Mosher 1982) and the distance to quality of foraging habitat may be more important than distance to nearest open water (MacDonald and Austin-Smith 1989).

Winter roosting habitat provides shelter from inclement weather and may be some distance from open water (Stalmaster 1987, Bueher 2000). Roost sites are located within micro-climates that protect bald eagles from harsh weather and conserves energy (Stalmaster 1987). Bald eagles will use either deciduous or coniferous trees, but selects large, super canopy roost trees that are accessible (Southern 1963, Buehler 2000).

Habitat Availability

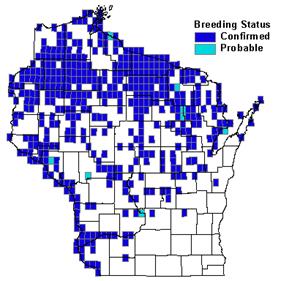

Bald Eagles were once widespread throughout North America (Stalmaster 1987) and throughout Wisconsin (Kumlien and Hollister 1903) in areas where lakes and rivers provided foraging habitat. Today, Bald Eagles breed on all the major lake and river systems in Wisconsin except for far southern, eastern, and southeastern Wisconsin. They do not breed on the Lake Michigan shoreline south of Door County (Eckstein et al. 2004).

Major breeding concentrations occur in the inland lakes region of north central and northwestern Wisconsin and along the Mississippi, Wisconsin, Chippewa, and Wolf river systems. Bald Eagles have returned to the Apostle Islands and the Lake Superior shoreline and nest in limited numbers on Lake Michigan’s Green Bay. Eckstein et al. (2004) report the top five Wisconsin counties with breeding pairs include Vilas (118), Oneida (103), Sawyer (61), Burnette (54), and Washburn (41).

Population Concerns

Historically, Bald Eagles were numerous in at least 45 of the contiguous 48 states and throughout Alaska and Canada ( Newton 1979). Bald Eagles bred throughout the state of Wisconsin and as the state became settled in the 1800s, eagle populations declined, caused by habitat destruction and shooting (Kumlien and Hollister 1903). By 1950, Bald Eagles were no longer breeding in southern two-thirds of Wisconsin, but remained stable in northern counties (WDNR unpubl. data). Bald Eagle populations reached their low points in the 1960s throughout the United States and Wisconsin due to the widespread use of toxic chemicals (DDT) and habitat destruction (Robbins 1991, Buehler 2000). In 1972, the Bald Eagle was placed on the Wisconsin Endangered Species List the same year the United States banded the use of DDT. In 1978 the Bald Eagle, in the contiguous 48 states, was listed as federally endangered except in Minnesota, Michigan, Wisconsin, Washington, and Oregon where it was listed as threatened (USFWS 1979). Since the banning of DDT and state and federal listing of the Bald Eagle, there has been a gradual increase of the 107 breeding pairs in 1974 to 880 breeding pairs in 2003 in Wisconsin (Eckstein et al. 2004). Today, the Bald Eagle is classified by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service as a Threatened Species in the lower 48 states. The Bald Eagle, as the national symbol, is protected under a special act of Congress, The Eagle Protection Act of 1940. In Wisconsin, WDNR classifies the Bald Eagle as a Species of Special Concern. Rapid development and human use of lake and river shoreline, aquatic invasive species, changing fish populations, emerging disease and environmental contaminant issues, and forestry practices near nest and roost sites are the major concerns that may affect the Wisconsin Bald Eagle population.

Recommended Management

To protect, monitor, and manage Wisconsin’s expanding Bald Eagle population a program to conserve nests, nesting and winter habitat, forage fish populations, and water quality is recommended. Use aerial surveys to locate nests and protect these nests utilizing buffer zones (Eckstein et al. 1997). Buffer zones to protect the nest tree, the area immediate surrounding the nest, and nearby alternate nest and perch trees. Work with private and public land managers to maintain large white and red pines adjacent to lakes and streams. Work with local, state, and federal officials to protect undeveloped lake and river shoreline through various land conservation initiatives. On the wintering grounds, protect roost sites along the lower Wisconsin and Mississippi rivers and tributary streams. Collect all Bald Eagle carcasses to assess mortality factors. Archive Bald Eagle tissue samples to assess environmental contaminants. Monitor wintering Bald Eagles along the lower Wisconsin River and assess the unknown agents causing periodic eagle mortality.

Research Needs

As a top of the food chain predator, the Bald Eagle has been used as an environmental sentinel to monitor the condition of aquatic resources and human developments near lakes and streams. A very large data set exists on Wisconsin Bald Eagle populations, productivity, and contaminant loads (Eckstein et al. 2004, Dykstra et al. 2004). Future research is dependent on long term monitoring of the population and periodic assessment of population and productivity trends in regions of the state where human developments, water quality issues, land use changes, and emerging disease issues may threaten Bald Eagles. Future research is needed to assess the impacts of extensive lakeshore development, invading aquatic species, emerging diseases, and changing water quality. There is also a need to continue to assess the impacts of the expanding Bald Eagle population on the distribution and abundance of Osprey in Wisconsin.

Information Sources

- http://www.fws.gov/midwest/eagle/

- http://www.baldeagleinfo.com

- http://magma.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0207/sights_n_sounds/media2.html

- http://www.nwf.org/wildlife/baldeagle/

- http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/id/framelst/:3520id.html

- http://www.dnr.state.wi.us/or/land/er/factsheets/birds/eagle.htm

References

- Andrew, J.M. and J.A. Mosher. 1982. Bald Eagle nest site selection and nesting habitat in Maryland. Journal of Wildlife Management. 46:383-390.

- Anthony, R.G., and F.B. Isaacs. 1989. Characteristics of bald eagle nest sites in Oregon. Journal of Wildlife Management. 53:148-159.

- Bent, A.C. 1961. Life histories of North American birds of prey. Vol. 1. Dover Publications, Inc. New York.

- Buehler, D. A. 2000. Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). In The Birds of North America, No. 506 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

- DellaSalla, D.A., R.G. Anthony, T.A. Spies, and K.A Engel. 1998. Management of Bald Eagle communal roosts in fire-adapted mixed-conifer forests. Journal of Wildlife Management. 62:322-333.

- Dykstra, C. R., M. W. Meyer, S. Postupalsky, K. L. Stromborg, D. K. Warnke, and R. G. Eckstein. 2004. Bald eagles of Lake Michigan: ecology and contaminants. In The State of Lake Michgan: Ecology, Health and Management (T. Edsall and M. Munawar, eds.) Ecovision World Monograph Series.

- Eckstein, R., G. Dahl, W. Ishmael, J. Nelson, P. Manthey, M. Meyer, S. Stubenvoll, and L. Tesky. 2004. Wisconsin Bald Eagle and Osprey surveys 2003. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI. 9 pp.

- Eckstein, R., S. Matteson, and P. Manthey. 1997. Bald Eagles in Wisconsin. A Management Guide For Landowners. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI. 15pp.

- Fraser, J.D., L.D. Frenzel, and J.E. Mathisen. 1985. The impact of human activities on breeding Bald Eagle in north-central Minnesota. Journal of Wildlife Management. 49:585-592.

- Grier, J.W. 1982. Ban of DDT and subsequent recovery of reproduction in Bald Eagles. Science. 218:1232-1235.

- Gostamski, T.J., and S.W. Matteson. 1999. Bald eagles nest in heron rookery in the Apostle Islands. The Passenger Pigeon. 61:155-159.

- Kumlien L. and N. Hollister. 1903. The birds of Wisconsin. Bulletin of the Wisconsin Hatural History Society 3 1-143; reprinted with A.W. Schorger’s revisions, Wisconsin Society for Ornithology. 1951.

- Livingston, S.A., C.S. Todd, W.B. Krohn, and R.B. Owen. 1990. Habitat models for nesting bald eagles in Maine. Journal of Wildlife Management. 54:644-653.

- MacDonald, P.R.N., and P.J. Austin-Smith. 1989. Bald Eagle, Haliaeetus leucocephalus; nest distribution in Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Canadian Field-Naturalist. 103:293-296.

- Mathisen, J.E., D.J. Sorenson, L.D. Frenzel, and T.C. Duncan. 1977. Management strategy for Bald Eagles. Trans. North America Wildlife and Natural Resource Conference. 42:86-92.

- McEwan, L.C., and D.H. Hirth. 1979. Southern Bald Eagle productivity and nest site selection. Journal of Wildlife Management. 43:585-594.

- Newton, I. 1979. Population ecology of raptors. Buteo Books, Vermillion, South Dakoda . 499 pp.

- Robbins, S.D., JR. 1991. Wisconsin birdlife, population and distribution, past and present. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison . 702pp.

- Southern, W.E. 1963. Winter populations, behavior, and seasonal dispersal of Bald Eagles in northwestern Illinois. Wilson Bulletin. 75:121-137.

- Stalmaster, M.V. 1987. The Bald Eagle. Universe Books, New York, NY

- Unite States Fish and Wildlife Service. 1979. List of endangered and threatened wildlife and plants. Federal Register 44:633-645.

- Warnke, D. K. 1996. A comparison of nesting behavior of Bald Eagles breeding along Western Lake Superior and adjacent inland Wisconsin. M.S. Thesis. The University of Minnesota. 58 pp.

- Wood, P.B., T.C. Edwards, and M.W. Collopy. 1989. Characteristics of Bald Eagle nesting in Florida. Journal of Wildlife Management. 53:441-449.

Contact Information

- Compiler: Dan Haskell, danhaskell@hotmail.com

- Editor: Ron Eckstein, Ronald.Eckstein@Wisconsin.gov