Status/Protection

- Global Rank: G5 Key to global and state ranks

- State Rank: S2B

- WBCI Priority: SGCN, WFOWL, State Special Concern

Population Information

The Federal BBS information can be obtained at http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html by clicking on Trend Estimates and selecting the species in question. All estimates are for time period (1966-2005).

*Note: There are important deficiencies with these data. These results may be compromised by small sample size, low relative abundance on survey route, imprecise trends, and/or missing data. Caution should be used when evaluating this trend.

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey: non-significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (WI): non-significant decline*

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 23): non-significant increase*

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 12): significant decline

- Midwinter Waterfowl Inventory: decline (1996-2006) (USFWS 2006)

- WSO Checklist Project: inverted u-shaped trend (1983-2007)

Life History

- Breeding Range: Manitoba east across Canada and northern U.S. to Atlantic Coast.

- Breeding Habitat: Emergent Marsh, Open Bog-Muskeg, Inland Open Water, Northern Sedge Meadow and Marsh, Alder Thicket, Shrub-Carr.

- Nest: Scrape; on ground lined with soft plant material.

- Nesting Dates: Eggs: Early May to early July (Robbins 1991).

- Foraging: Dabbles.

- Migrant Status: Permanent resident/Short-distance migrant.

- Habitat use during Migration: Great Lakes Open Water, shallow forested wetlands, riverine marshes, floodplain pools, lakes, ponds, beaver-mediated wetlands, and reservoirs.

- Arrival Dates: Mid-March to early May (Robbins 1991).

- Departure Dates: Mid-September to mid-December (Robbins 1991).

- Winter Range: Winters mainly from southern portion of breeding range south to Gulf Coast and the northern half of Florida; at many locations around the Great Lakes; west to sw. Iowa and se. Nebraska, e. Arkansas, and Mississippi (Longcore et al. 2000).

- Winter Habitat: Palustrine emergent wetlands, beaver ponds, flooded timber, riverine habitats, and agricultural fields inland; salt marsh and tidal habitats are essential in coastal areas (Longcore et al. 2000).

Habitat Selection

Although there are Wisconsin breeding records for American Black Duck, it is not a common breeder anywhere in the state (Robbins 1991, Bub and Gregg 2002, Verch 2006). Throughout its range, it breeds in a wide variety of riparian habitats including freshwater wooded swamps, beaver-created and modified wetlands, bogs in boreal forests, and smaller alder-lined brooks in northern-forested regions (Fannes 1981, Longcore et. al 2000). Nest sites often contain a high degree of interspersed emergent vegetation and open water (Steven et al. 2003). In Wisconsin, it nests in open lowland marshes and lakes (Verch 2006), often preferring larger waters (Bub and Gregg 2002). Food resources consumed during the breeding season include aquatic insects, crustaceans, mollusks, and the seeds of various terrestrial and aquatic plants (Longcore et. al 2000, Bellrose 1976). Scattered individuals and small flocks frequently winter in open water areas of Wisconsin (Robbins 1991) where they feed on roots, tubers, stems, and leaves of moist soil and aquatic plants (Longcore et. al 2000, Bellrose 1976).

Habitat Availability

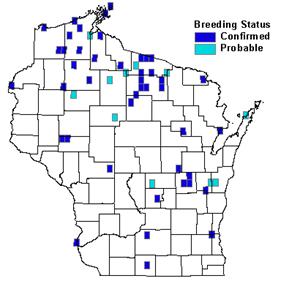

Wisconsin lies on the western edge of the American Black Duck’s breeding range. Most breeding activity is concentrated in the numerous lakes of northeastern Wisconsin forests and interior portions of the state north of a line from St.Croix through Eau Claire, Marathon, Shawano, and Marinette counties (Jahn and Hunt 1964, March et al. 1973, Longcore et al. 2000). However, evidence of nesting activity has been documented in numerous counties south of this line, including Brown, Columbia, Dane, Dodge, Jefferson, and Manitowoc counties (Peterson et. al 1982, J. March, pers. comm.). The distribution of American Black Ducks during spring and fall migration is statewide, but most birds concentrate in the eastern half of the state, southeast of a line from Waupaca through Columbia, Dane, and Rock counties (Jahn and Hunt 1964, Robbins 1991). Wisconsin has wintering records for American Black Ducks throughout the state. Most wintering individuals are sedentary and only move short distances inland as wetlands thaw in spring (Longcore et. al 2000).

Prior to Euro-American settlement, wetlands occupied an estimated four million hectares of the total fourteen million hectares of Wisconsin’s land area. Today, 53%, or 2.1 million hectares, of these wetland habitats remain. Strict wetland use regulations and incentive programs designed to restore or enhance wetlands have helped to curb habitat loss and protect existing wetlands (WDNR 1995). Additionally, the Upper Mississippi River/Great Lakes Region Joint Venture has protected, enhanced, or restored more than 51,000 hectares of upland habitat in Wisconsin as well as 37,000 hectares of wetland habitat. Agricultural drainage and urban development remain threats to wetland ecosystems and local populations of wetland-associated birds. Human activities that alter hydrology and introduce invasive plant species also threaten wetland habitats (WDNR 2003). Also, beaver control programs in northern Wisconsin may reduce the habitat suitability in some areas.

Population Concerns

Regional breeding population data for American Black Duck are limited. In the forested areas of northern Wisconsin, total duck production has been difficult to assess given the large amounts of habitat, discontinuous use by breeding ducks, and the difficulty of surveying forested regions by air (WDNR 1992). Breeding birds were not numerous in any areas surveyed by Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas workers. Only five nests were found during the Atlas period (1995-2000; Verch 2006). During the Wisconsin Waterfowl Breeding Population Survey of 2006, American Black Ducks were not detected; however, they were detected in the 2005 survey and have occurred regularly in small numbers during previous years (Van Horn et al. 2005, Van Horn et al. 2006).

Most historical population information about this species is based on surveys of wintering populations such as the Midwinter Inventory (MWI; Link et al. 2006). American Black Duck population declines were noted beginning in the mid-1950s (Longcore et al. 2000). In 1983 restrictive regulations substantially reduced the harvest of birds and helped to stabilize the downward trend (Longcore et. al 2000). MWI counts in 2006 (Mississippi and Atlantic Flyway data combined) increased 2% relative to 2005 counts, but remained 18% lower than the 10-year mean (USFWS 2006). Christmas Bird Counts provide extensive data from regions not covered by other winter surveys and have shown similar large-scale patterns of population change compared to MWI data (Link et al. 2006).

The ability to track changes in wintering Black Duck populations is confounded by indications that black ducks may be wintering further north in largely unsurveyed areas, possibly a consequence of climate change. Some biologists suggest that population declines measured in winter surveys may be offset by increases in other regions. The MWI in the Mississippi Flyway experienced a decline in 1997 from which it has not rebounded while in the Atlantic Flyway numbers have been stable since 1980 (Mississippi/Atlantic Flyway Black Duck meeting minutes June, 2006). Because winter season data are primarily used to track population changes, definitive information on the cause of change is not known (Link et al. 2006). Hunting, habitat loss, and hybridization or competition with Mallards may be contributing to regional changes (Conroy et al. 2002). Although the ultimate effects are still unknown, hybridization is thought to be the most critical for populations that are geographically isolated, heavily exploited by hunters, or severely limited by habitat availability (Young et al. 1997, cited in Longcore et al. 2000).

Recommended Management

Wetland management for American Black Duck should focus on increasing open water areas, while preserving some cattail cover (>14%) to provide refuge from predators. In addition, restoring wetlands near freshwater rivers (<160 meters) may provide movement corridors for American Black Duck broods (Stevens et al. 2003). Water drawdowns that encourage growth of mudflat annuals, regenerate stands of emergent vegetation, stimulate primary productivity, and in turn improve the detrital base are beneficial for many species of wetland wildlife and should benefit American Black Ducks as well (Kenow and Rusch 1996).

Conservation and management strategies should be focused in the following ecological landscapes: North Central Forest, Northern Highland, Northern Lake Michigan Coastal, Northwest Sands, Southeast Glacial Plains, and Superior Coastal Plain (WDNR 2005). Horicon National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) in Dodge County, Grand River Marsh Wildlife Area in Green Lake County, Crex Meadows Wildlife Area in Burnett County, and marshes surrounding Poygan, Winneconne, and Butte des Morts lakes in Winnebago County are important breeding and stopover sites (Fannes 1981, Wheeler et al. 1984, Robbins 1991, WDNR 1992). Important wintering areas include Turtle Creek in Walworth County, Spring Brook Farms in Dodge County, Bay Beach Sanctuary in Brown County, Madison, Milwaukee, and Neenah area lakes, Green Bay, and the lower St. Croix River (Jahn and Hunt 1964, Fannes 1981, Robbins 1991, WDNR 1992, Evrard 2002).

Research Needs

More research is needed on the ecological factors limiting American Black Duck productivity, such as predation, habitat characteristics, and nutrient availability in the species core breeding range. The extent and degree of American Black Duck/Mallard interactions across the range of breeding, staging, and wintering habitats needs to be better understood. Studies that examine methods for effectively managing important staging and wintering habitats are warranted (USFWS 1993).

Information Sources

- Black Duck Adaptive Management Working Group: http://coopunit.forestry.uga.edu/blackduck/

- Black Duck Joint Venture Strategic Plan: http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/bdjv/bdjvstpl.htm

- Chequamegon National Forest Bird Survey (NRRI) species account: http://www.nrri.umn.edu/mnbirds/accounts/ABDUa2.htm

- Jahn L.R. and R.A. Hunt. 1964. Duck and coot ecology and management in Wisconsin. Technical Bulletin (33): 1-212. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison.

- Kahl, R. 1991. Restoration of canvasback migrational staging habitat in Wisconsin: a research plan with implications for shallow lake management. Technical Bulletin (172): 1-47. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison.

- Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas http://www.uwgb.edu./birds/wbba/

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). 1992. Upper Mississippi River and Great Lakes region joint venture- Wisconsin plan. Madison, WI.

References

- Bellrose, F.C. 1976. Ducks, geese, and swans of North America. Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, PA.

- Bub, B.R. and L.E. Gregg. 2002. Summary of waterfowl brood surveys in northern Wisconsin, 1987-1991. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Final Report. Study No. 319.

- Conroy, M.J., M.W Miller, and J.E. Hines. 2002. Identification and synthetic modeling of factors affecting American Black Duck populations. Wildlife Monographs 150.

- Evrard, J.O. 2002. Duck production and harvest in St. Croix and Polk counties, Wisconsin. Technical Bulletin 194: 1-38. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI.

- Faanes, Craig A. 1981. Birds of the St. Croix River Valley, Minnesota and Wisconsin. U.S. Department of the Interior. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. North American Fauna, Number 73. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Home Page. http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/1998/stcroix/stcroix.htm (Version 31JUL98).

- Jahn L.R. and R.A. Hunt. 1964. Duck and coot ecology and management in Wisconsin. Technical Bulletin 33: 1-212. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI.

- Kenow, K.P. and D.H. Rusch. 1996. Food habits of Redheads at the Horicon Marsh, Wisconsin. J. Field Ornithol. 67(4): 649-659.

- Link, W.A., J.R. Sauer, and D.K. Niven. 2006. A Hierarchical Model for Regional Analysis of Population Change Using Christmas Bird Count Data, with Application to the American Black Duck. Condor 108(1): 13-24.

- Longcore, J.R., D.G. McAuley, G.R. Hepp, and J.M. Rhymer. 2000. American Black Duck (Anas rubripes). In The Birds of North America, No. 481 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

- March, J.R., G.F. Martz, and R.A. Hunt. 1973. Breeding duck populations and habitat in Wisconsin. Technical Bulletin (68): 1-36. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison.

- Robbins, S.D., Jr. 1991. Wisconsin birdlife: Population and distribution past and present. Madison, WI: Univ. Wisconsin Press.

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 1993. Final Draft-Strategic Plan. Black Duck Joint Venture, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service/Canadian Wildlife Service. http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/bdjv/bdjvstpl.htm

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). 2006. Waterfowl population status, 2006. U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. U.S.A.

- Van Horn, K., K. Benton, and R. Gatti. 2006. Waterfowl breeding population survey for Wisconsin, 1973-2006. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI. 37pp.

- Verch, D. 2006. American Black Duck. In Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Wisconsin. (N.J. Cutright, B.R. Harriman, and R.W. Howe, eds.) The Wisconsin Society for Ornithology, Inc. 602pp.

- Wheeler, W.E., R.C. Gatti, and G.A. Bartelt. 1984. Duck breeding ecology and harvest characteristics on Grand River Marsh wildlife area. Technical Bulletin (145): 1-49. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison.

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). 1992. Upper Mississippi River and Great Lakes region joint venture- Wisconsin plan. Madison, WI.

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). 1995. Wisconsin’s Biodiversity as a Management Issue. http://dnr.wi.gov/org/land/er/biodiversity/report.htm

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) Wetland Management Team. 2003. Reversing the loss: A strategy for protecting and restoring wetlands in Wisconsin. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI. http://dnr.wi.gov/org/water/fhp/wetlands/documents/reversing.pdf

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). 2005. Wisconsin’s Strategy for Wildlife Species of Greatest Conservation Need. Madison, WI.

- Young, H.G., S.J. Tonge, and J. P. Hume. 1997. Review of Holocene wildfowl extinctions. Wildfowl 47: 166–180.

Contact Information

- Compiler: Steven C. Houdek, steve_houdek@usgs.gov

- Editor: Kim Kreitinger, K.Kreitinger@gmail.com