Photo 1 | Photo 2 | Photo 3 | Photo 4 | Photo 5 | Photo 6

Habitat Description

Habitat Crosswalk

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Silviculture Handbook: Bottomland Hardwood, Swamp Hardwood (WDNR 2010).

- Kotar Habitat Type: Southern Habitat Type Group 14, Wet-mesic to Wet (WM-W). (Kotar and Burger 1996); Note: There have not been any habitat types developed for this group.

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Natural Communities: Floodplain Forest, Southern Hardwood Swamp (WDNR 2005).

- USDA Forest Service, Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA): Elm/Ash/Cottonwood Group (http://fia.fs.fed.us/).

- Vegetation of Wisconsin: Southern Wet Forest; Southern Wet-mesic Forest (Curtis 1959).

- Wisconsin Wetlands Inventory: Forested, Deciduous and Broad-leaved Deciduous (WDNR 1992).

- Cowardin: Palustrine, Forested Wetland, Broad-leaved Deciduous (Cowardin et al. 1979).

- Shaw and Fredine: Type 7; Inland Fresh, Wooded Swamp (Shaw and Fredine 1971).

Introduction

Bottomland hardwoods occur along rivers and streams, mainly in the southern half of the state but also at scattered locations in the north. The largest tracts are found along the Mississippi and lower Wisconsin Rivers, with significant stands also occurring on the Chippewa, Black, Yellow, Baraboo, Wolf, Sugar, Rock, St. Croix, and lower Peshtigo. Small stands are found along many rivers and streams (Mossman 1988). Important canopy species include silver maple, green ash, river birch, swamp white oak, red maple, black willow, cottonwood, and hackberry. Several tree species more typical of the southern U.S., such as sycamore, honey locust, and Kentucky coffee tree can be found locally among bottomland hardwoods in southern Wisconsin. American elm, formerly an important canopy species in these forests, has been greatly reduced by Dutch elm disease and now rarely reaches the canopy before succumbing, although young trees are still fairly common. Common understory species, often occurring in a patchy distribution, are wood nettle, jewelweed, sedges and grasses, green dragon, cardinal flower, and green-headed coneflower. Vines such as woodbine, poison ivy, wild grape, moonseed, and wild cucumber can be prominent. Canopy openings may be invaded by thickets of native shrubs such as prickly ash and dogwoods, while sloughs and the margins of oxbow ponds often have the water-loving buttonbush.

A related forest type, swamp hardwood (lacustrine swamp or NHI’s southern hardwood swamp), occurs in isolated lowland basins and sometimes lakeshores. It often is dominated by red maple and ashes, including black ash, with a prevalence in the understory of ferns and shrubs such as dogwoods, nannyberry, and alder. This forest type is influenced by standing water (seasonally high water table or inundation during spring runoff or major precipitation events) rather than by flood waters that flow through the stand, a hydrologic difference that leads to growth rates and understory composition distinct from bottomland hardwoods (WDNR 2011). Some streamside tracts have characteristics that are intermediate between these two major forest types (e.g., dominated by swamp white oak and black ash).

Bottomland hardwood forests typically vary in structure and composition at both local and landscape scales due to the effects of variations in topography, soils and hydrology, and natural processes such as beaver activity and windthrow. Indeed, many such forests are naturally interrupted by sloughs, ponds, shrub swamps and meadows, and by even drier barrens habitats on sandy terraces, but these habitats are often interconnected in extensive mosaics with gradual, natural ecotones. More so than upland forests, which today tend to be separated from other habitats by hard, artificial edges, bottomland hardwoods may best be seen as a dynamic component of a larger ecosystem.

In general, wet floodplain sites tend to be dominated by silver maple and green ash. River birch is sometimes common, especially along the lower Wisconsin and Mississippi rivers and the lower reaches of their tributaries. Active or deadwater sloughs, stream and river channels that often interrupt floodplain forest cover, are overhung to varying extents by the spreading, hanging canopies of silver maple or cottonwood, and formerly American elm. Higher, wet-mesic sites have these same species but with increased prevalence of swamp white oak, hackberry, white ash, basswood, and (on higher, sandier terraces) black oak and sometimes white pine. With fewer openings than wet forests, and more prevalent shrub and sapling layers, wet-mesic forest structure tends to resemble that of upland forest. In areas of former glacial lakes (e.g., Central Sand Plains and Hills), or along the conduits that drained them (e.g., Lower Chippewa and especially Lower Wisconsin), terraces can be sandy, and xeric for much of the year, adding an additional component of “river barrens” (Sample and Mossman 1997) to the floodplain mosaic, characterized by sparse cover of grasses and forbs, open sand, river birch, green ash, red cedar and black oak. On some expansive terraces with deep, sterile sands, these species are joined by jack pine and sand prairie herbs.

Newly exposed wet soil tends to be pioneered by thickets of sandbar willow shrubs, black willow, river birch and cottonwood, while thicker or higher, somewhat drier deposits on higher terraces often are invaded by river birch, cottonwood, green ash, oaks and prickly-ash.

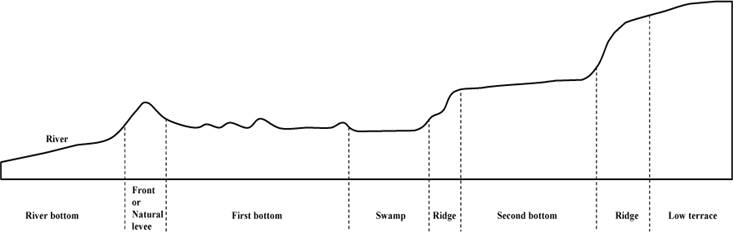

Figure 1 illustrates typical physiographic relationships among floodplain habitat types. At any point along a river, the cross-section may exhibit only some of these features, and in some cases rises immediately to upland cliffs or bluffs.

- River bottom: open water; exposed sand or mud bars or banks that are free of vegetation or pioneered by herbs, sandbar willow, river birch, silver maple, or cottonwood; wooded islands.

- Front levee: wet-mesic forest or river barrens.

- First bottom: wet forest, wet-mesic forest, swamp white oak savanna or woodland, often with sloughs interspersed; black oak occurs on some high sandy ridges in the Central Sands.

- Swamp: emergent marsh, shrub-carr, alder swamp, sedge meadow, wet prairie.

- Ridge: ecotone.

- Second bottom: wet-mesic forest; wet-mesic oak-pine forest in Central Sands; swamp white oak savanna.

- Ridge: ecotone.

- Low terrace: wet-mesic forest; wet-mesic oak-pine forest in Central Sands; oak forest or central hardwoods; scrub oak; river, oak or pine barrens; upland oak savanna; sand prairie; cropland.

Historical and Present-day Context and Distribution

Acreage estimates for presettlement and current bottomland hardwood forests vary considerably according to definitions and methods, although all accounts acknowledge its limited distribution and extent, and further, that swamp hardwoods were and remain much less common than bottomland (floodplain) hardwoods. Curtis (1959) considered that both types comprised 420,000 acres (1.2% of the Wisconsin land area) prior to Euro-American settlement, and that 290,000 acres (69% of presettlement) was estimated by the Land Economic Inventory during 1933-47. Mossman and Matthiae (1988) stated that only 32,000 acres (8%) remained in moderate to high quality stands. Recent estimates from Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) data from Wisconsin estimate 464,000 acres of floodplain and swamp hardwood forest statewide, but based on what may be an inadequate sample. The best statewide estimate is probably that of the Wisconsin Wetlands Inventory: 686,000 acres. (Calvin Lawrence WDNR, pers. comm., 3 May 2011).

Although these forests have fared better than other native communities in Wisconsin due to the difficulty of converting them to other land uses, they still have declined greatly in extent since European settlement. Remaining tracts have been fragmented and degraded by a variety of human activities including high-grade logging, grazing, ditching, clearing for agriculture, invasion by exotic species, and alteration of flood regimes on many streams and rivers due to dam construction, road construction, channelization, wetland drainage, and urban development (Mossman 1988; WDNR 2011). Some new floodplain forest has developed since European settlement due to succession on meadow and oak savanna sites (sometimes after a period of cultivation), facilitated by reduced flooding and the absence of fire.

The largest tracts of bottomland hardwoods occur in southern Wisconsin in the Western Coulee and Ridges Ecological Landscape, with significant acreages also found in the Central Sand Plains and Southeast Glacial Plains. Other Ecological Landscapes that contain important sites are: Central Lake Michigan Coastal; Central Sand Hills; Forest Transition; North Central Forest; Northern Lake Michigan Coastal; Northwest Lowlands; Superior Coastal Plain; and Western Prairie (WDNR 2008a).

Hardwood swamps have suffered from drainage, ditching, siltation, excessive nutrient input, and overharvest and remain in much smaller tracts than bottomland hardwoods. Isolated tracts occur nearly statewide. Northward and in the Central Sand Plains they often are associated with and grade into coniferous and mixed swamps.

Natural Disturbances and Threats

Bottomland hardwoods and other floodplain habitats are adapted to—and driven by—disturbance. Periodic flooding, particularly in spring, is the primary natural disturbance that historically has shaped this community. The frequency, timing, duration, and extent of flooding can alter floodplain topography and influence the species composition and structure of both canopy and understory vegetation layers. Flooding can cause scouring effects from water, ice, and debris that damage or remove vegetation and expose sand or mud on spits or slough margins, can leave tangles of dead branches and other detritus, and can deposit sediments containing nutrients and organic matter that alter the microtopography of the floodplain. Floods can also carry in seeds and other propagules of plant species (WDNR 2008a; Mossman 1988; WDNR 2011). Many bottomland tree species are early-successional and are adapted to exploit the conditions created by periodic floods. Bottomland hardwoods tend to be fast-growing, utilizing the relatively high levels of nutrients and moisture supplied in floodplains to maintain rapid growth. Several species take advantage of, or require, bare soil for seed germination. For example, silver maple requires a fresh deposit of silty soil as a seedbed. Flooding affects stand structure by influencing the survivorship of seedlings based on their location in the floodplain. Seedlings that become established on the higher elevations of a floodplain are more likely to survive the effects of subsequent floods than those established on the lower elevations. At lower elevations this can result in stands with widely spaced canopy trees and sparse woody understory, with a dense groundlayer of wood nettles and a few other herbs that respond quickly to floodwater recession. Higher sites typically exhibit more regeneration, a denser shrub layer, and a more diverse herbaceous layer.

Other natural disturbances shape the structure, composition and landscape pattern of bottomland hardwoods as well. Most of the common tree species are shallow-rooted and subject to throw by windstorms, which can be funneled along river valleys. Canopy disturbance can range from minor to severe, depending on the wind event. Beaver can fell saplings and even large canopy trees, and create impoundments that flood out forest tracts, which may, after drainage, persist as open meadows. Historically, fire was necessary to maintain floodplain savannas (typically dominated by swamp white oak or bur oak), black oak-jack pine barrens on more xeric terraces, and some marshes, meadows and shrub swamps that characteristically interrupt forest cover, especially near uplands. In Wisconsin, fire has been frequent both historically and currently in portions of the lower Chippewa, lower Black, and lower Wisconsin rivers, and formerly occurred on the Mississippi. Stands on sand and gravel may be predisposed to fire after periods of seasonal drought (Curtis 1959; WDNR 2008b).

Threats to bottomland hardwoods include altered hydrology, exotic species, excessive herbivory, and conversion, fragmentation, and degradation of the habitat due to a variety of human activities. Threats to hydrology are of primary significance as the hydrologic regime is such a defining feature of this community, affecting many of its physical characteristics. Dam and impoundment construction on many rivers and streams has affected the timing, frequency, duration, and magnitude of flood events, thus altering the major natural disturbance to which bottomland hardwoods are adapted, with consequences for species composition and structure, and future successional pathways (WDNR 2008a). This type of flow regulation often is characterized by flooding that is less extreme but more frequent than that experienced under a natural flood regime, resulting in a lack of erosion and deposition that creates ‘new land’ where early-successional species can thrive, or more frequent inundation of stands that does not allow trees to become established. A lack of severe flooding may be leading to community succession based not on flood tolerance, as is the case under more natural flood regimes, but on shade tolerance. For example, reduced flooding on the lower Wisconsin River has resulted in the loss of early-successional or “pioneer” species such as cottonwood and black willow and a shift to a later-successional stage dominated by silver maple and Central Hardwoods species such as bitternut hickory and hackberry which were not historically dominant (Hale et al. 2008). Artificially high water levels created by impoundment in Upper Mississippi River floodplain forests have replaced large forest tracts with open water, while in remaining stands eliminated less flood-tolerant species such as green ash, swamp white oak, and hackberry and creating near monocultures of the more flood-tolerant silver maple, often in even-aged stands (Knutson and Klaas 1998).

Exotic diseases and insects also have affected species composition and structure. Dutch elm disease has virtually eliminated American elm as a canopy dominant, opening up the canopy in many bottomland hardwood forests and leaving gaps that in some cases have yet to fill in with trees (Mossman 1988; WDNR 2008a). Elms were abundant, sometimes very large, and had distinctive limb architecture, so their loss has affected stand structure. An introduced insect, the emerald ash borer, is expanding its range in Wisconsin and threatens the ash component of the bottomland hardwood community. Another introduced insect, the gypsy moth, threatens oaks and other species (WDNR 2008a).

The exotic, highly invasive reed canary grass is a major threat to bottomland hardwoods, spreading quickly after a disturbance that opens the canopy, such as timber harvest, windthrow, or disease. It can quickly dominate the ground layer and impede tree regeneration. Other problematic invasive plants are moneywort, creeping Charlie, common and glossy buckthorns (on wet-mesic sites) and, potentially, common reed (Phragmites).

Bottomland hardwoods have been reduced in extent by clearing for agriculture and development or conversion to other habitat types (e.g., conversion to marsh or shrub wetlands due to dike construction). Existing tracts can be degraded by neighboring land uses (e.g., altering the flood regime, pollution or sedimentation from adjacent agriculture or construction) and unsustainable logging and grazing. Excessive herbivory by white-tailed deer or domestic livestock can alter the composition of understory layers, impede tree regeneration, and contribute to the spread of invasive species such as prickly ash and buckthorn. Unsustainable forest management practices can fragment habitat, alter species composition, and facilitate the spread of invasive plants (WDNR 2008a; Hale et al. 2008).

While Wisconsin’s climate is changing, displaying increases in seasonal temperatures and average annual precipitation over the past 60 years (WICCI 2011), specific effects of these changes on bottomland communities are difficult to predict. However, the increased probability of more extreme disturbance events, such as heavy downpours that lead to rapid, severe, more frequent or midsummer flooding (Easterling et al. 2000, Jentsch et al. 2007) may have negative consequences for floodplain systems.

A useful definition of a “healthy” or “high quality” forest stand or ecosystem is more elusive for bottomland hardwoods than for most other forest types, considering the uncertainties associated with the long-term effects of important drivers such as: climate change; exotic invasive plants, insect pests and diseases (which have and may continue to eliminate major tree species from the canopy); watershed inputs; and dams (even those that have been in place for many decades). How will a system dependent on flood regimes—and to a lesser extent on fire, windstorm and beaver activity—respond to this complex of changing influences, most of which are beyond the pale of local forest and habitat managers? The future of bottomland hardwoods and its associated communities will be best served by a conservative and integrated approach to management that considers the floodplain system and its watershed as a whole, with a long-term perspective that guides monitoring, experimentation, and research. High quality stands thus include those with intact native flora and fauna, but also those with resilience afforded by size, connectivity, natural ecotones with associated floodplain and upland communities, and limited hydrological disturbance within watersheds and from upriver dams.

Related WBCI Habitats: Shrub-carr, Alder Thicket, Oak Barrens, Oak Opening.

Overall Importance of Habitat for Birds

Bottomland hardwoods in Wisconsin comprise some of the largest remaining forested tracts south of the Tension Zone and support a rich and diverse avifauna (Mossman 1988; Knutson et al. 1996; Miller et al. 2004). Knutson et al. (1996) reported that species richness and relative abundance of birds in Upper Mississippi River floodplain forests were almost twice as high as those in adjacent upland forests. Common breeding species are Great Crested Flycatcher, Eastern Wood-Pewee, Song Sparrow, House Wren, American Robin, American Redstart, Baltimore Oriole, Downy Woodpecker, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, and Blue Jay. Other less common but characteristic bottomland hardwood species, more abundant in this habitat than in most or all other habitat types in Wisconsin, include Yellow-crowned Night-Heron, Wood Duck, Red-shouldered Hawk, Barred Owl, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Tufted Titmouse, Brown Creeper, Warbling Vireo, Prothonotary Warbler, and Kentucky Warbler. Large tracts of bottomland hardwoods provide important habitat for area-sensitive species, including Red-shouldered Hawk, Acadian Flycatcher, Wood Thrush, Cerulean Warbler, and Kentucky Warbler, particularly where they occur adjacent to extensive tracts of upland forest. The bottomlands of the Sugar River in far southern Wisconsin where sycamores and other southern tree species extend northward into the state have been an important breeding site for Yellow-throated Warbler (Hansen 2006), an uncommon southern species that also occurs in several upland oak-pine sites in the state. Although the species has been absent from this area in recent years, it may occur again if climate change causes further northward range shifts of southern tree species into Wisconsin.

The bottomland hardwood avifauna has various distinctive features. Fish-eating birds, including herons, egrets, Bald Eagle, Osprey, Belted Kingfisher, and Hooded Merganser are well represented. The large number of dead or dying trees killed by flooding or disease supports a high proportion of cavity nesters, bark gleaners, and wood drillers, including Great Crested Flycatcher, Brown Creeper, Prothonotary Warbler, and 7 of Wisconsin’s 8 breeding woodpeckers. Red-headed Woodpecker, a species more typically associated with savannas, nested frequently in dead elms in the bottomlands. Although no longer as common in this habitat with the collapse of many dead elms, mortality of ashes with invasion by emerald ash borer may make this species prevalent in the bottomlands once again. Bottomland hardwoods also host many cliff-nesting species such as Bank, Barn, Cliff, and Northern Rough-winged Swallows and Belted Kingfisher due to their proximity to cliffs, cutbanks, and bridges (Mossman 1988). Their location along major river corridors also makes bottomland hardwoods critical habitat for migrating birds, particularly landbirds, in both fall and spring. Bottomland hardwoods are the main migratory habitat for Rusty Blackbird, the only Wisconsin priority species identified solely on the basis of its presence during migration.

WBCI Priority Bird Species. Species in boldface are currently proposed as Focal species for southern Wisconsin forests.

Species name Status Habitat and/or Special Habitat Features Mallard bMwf Generalized, more near urban and open habitats. Hooded Merganser BMwF Deep sloughs; nest in snags. Ruffed Grouse bwf Now rare; wet-mesic; where patches of both early-successional and older forest. Great Egret bMF In extensive floodplain systems of forest-marsh-river-slough-pool; colonies rare, nest with GTBH, may travel far to forage; more widespread before and after nesting season. Yellow-crowned Night-Heron bmf In extensive floodplain systems of forest-marsh-river-slough-pool. Bald Eagle BMWF Nest in supercanopy trees; forage on fish in main and side channels, feeder streams, also on upland carrion in winter. Red-shouldered Hawk BMwF In extensive mature floodplain forest tracts with small pools, sloughs; nest in large trees, sometimes in adjacent upland forest. American Woodcock bmF In early-successional tracts, large openings, and shrub-carr. Black-billed Cuckoo bM Mostly migrant; breeds in some shrub-carr, woods edge. Yellow-billed Cuckoo BM Common but erratic in most floodplain forest tracts >40 acres. Whip-poor-will bm Disappearing; occurs in wet-mesic sites, more commonly in adjacent barrens or oak woodland. Chimney Swift bmF Nest in chimneys, occasionally in large “chimney” snags; commonly forage over and within floodplain forest of all types. Belted Kingfisher BMwF Nest in exposed riverbanks and cliffs, adjacent upland cliffs and cutbanks; forage extensively in channels and sloughs. Red-headed Woodpecker bmwf Where barkless snags occur due to flooding or disease; also in open-canopy patches. Yellow-bellied Sapsucker BMw Widespread, especially associated with river birch; nests in cavities in snags and live trees. Northern Flicker BMw Scattered, where snags, open or semi-open canopy, open herbaceous understory, often using both floodplain forest and adjacent uplands. Acadian Flycatcher bm Occasional along smaller rivers or at boundary of extensive upland and floodplain forest (especially bases of steep slopes). Willow Flycatcher bm Shrub carr, most common where least forested. Least Flycatcher bM Scattered, often in colony-like breeding groups, in both interior and edge. Yellow-throated Vireo BM Common and widespread in mature forest tracts >40 acres. Warbling Vireo BM Mostly in forest edge, scattered mature trees, edges of forest sloughs, especially where canopies are spreading or overhanging. N. Rough-winged Swallow BM Nest in exposed riverbanks and cliffs, adjacent upland cliffs and cutbanks, artificial structures, tip-ups; forage extensively over forest, channels and sloughs; usually nest singly or in small groups, or in Bank Swallow colonies. Bank Swallow BM Nest in colonies in floodplain and upland cutbanks and cliffs, sand pits. Veery BM Wet-mesic forest where there are dense shrubs or rank, tall, diverse forest herb layer. Wood Thrush BM Wet-mesic and adjacent upland forest in tracts >40 acres; territories often include patches of tall semi-dense saplings. Brown Thrasher bm Sandy open areas, adjacent open upland grassland and barrens. Blue-winged Warbler BM Wet-mesic, shrubby forest openings, edges and upland-floodplain boundary. Golden-winged Warbler bm Rare; in same sites as Blue-winged Warbler. Chestnut-sided Warbler bM Rare breeder, in shrubby forest openings, edges and upland-floodplain boundary. Yellow-throated Warbler bm Formerly among sycamores along Sugar River and possibly lower Wisconsin and Mississippi rivers; only recent records are from upland oak with supercanopy white pine. Cerulean Warbler BM Mature forest with diverse canopy species and structure, much more likely where adjacent to extensive upland forest; entire patch must be >240 acres. Prothonotary Warbler BM Wet forest with sloughs, low snags; more abundant and generalized (less limited to sloughs) near Wis/Miss River confluence. Louisiana Waterthrush bm Territories always include suitable adjacent upland or floodplain-forest boundary, where stream gorges or springs enter floodplain. Kentucky Warbler BM Wet-mesic forest and floodplain-upland boundary, where suitable upland-floodplain forest tract >240 acres; often in dense or semi-dense shrubby openings of natural or logging origin. Mourning Warbler bm Similar to Kentucky Warbler, but more common, less restricted to large tracts, extends into larger open-canopy patches Common Yellowthroat BM In large forest openings, along edges of rivers, large sloughs and shrub-carr and marsh, more so in wet than wet-mesic sites. Swamp Sparrow bm Shrub carr, adjacent forest edge, and larger patches of shrub adjacent to large open sloughs. Rose-breasted Grosbeak BM Common and widespread in forest interior or edge; prefers open or semi-open canopy with moderate sapling/shrub growth. Rusty Blackbird mwf Declining migrant, much more common in floodplain forest than elsewhere; forages in small vernal pools and wet leaf litter.

Objectives

The Upper Mississippi River and Great Lakes Joint Venture (UMRGLJV) 2007 Implementation Plan assigns Wisconsin a habitat objective for the bottomland hardwood cover type (Forested Wetland) of 741 acres for Management and Protection and 247 acres for Restoration and Enhancement, using Prothonotary Warbler as a focal planning species. These objectives are based on BCR 23 and Wisconsin Prothonotary Warbler population estimates and goals that are extremely low because they are extrapolated from data of the federal BBS, a survey that does not sample bottomland habitats, or relatively rare species like Prothonotary Warbler, well. Without a reliable estimate of Prothonotary Warbler populations in Wisconsin it is difficult to set a numeric habitat objective for bottomland forests based on this species. The WBCI Southern Forests committee recommends generating a better estimate, but in the interim, the committee suggests a goal to increase Prothonotary Warbler and other focal species populations within bottomland forests in the Wisconsin portion of BCR 23.

Wisconsin holds the most extensive and high-quality floodplain forests in BCR 23, and the entire Great Lakes region, which affords both opportunity and responsibility. Certainly, a more complete assessment is needed for this community, its birdlife and the sites, species and management issues most worthy of attention.

Management Recommendations

Landscape-level Recommendations

- Maintain and protect existing large (>10,000 acres), contiguous tracts of bottomland hardwoods, particularly where they exist adjacent to large tracts of upland forest (Knutson et al. 2001; LMVJV Forest Resource Conservation Working Group 2007; WDNR 2008a; M.J. Mossman, pers. comm. 2011).

- Maintain and protect high-quality examples of bottomland hardwoods of any size, particularly when adjacent to other intact habitats. Many of the recommendations below for increasing connectivity should be targeted in and around these high-quality remnants.

- Wherever possible, use forested corridors to link large blocks and high-quality remnants of forest, and to provide for species migration due to climate change (LMVJV Forest Resource Conservation Working Group 2007).

- Where feasible, restore natural hydrologic regimes (Knutson et al. 1996).

- Manage bottomland hardwood forests as part of existing natural mosaic of floodplain habitats and ecological gradients from lowlands to uplands (WDNR 2008a).

- Use buffers to protect floodplain systems from negative impacts of upstream land uses (e.g., sedimentation, pollution) (WDNR 2008a).

- Widen floodplain corridors where feasible, particularly to incorporate natural ecological gradients (e.g., by reforesting reclaimed agricultural land) (Knutson and Klaas 1998).

- Maintain or provide a diversity of tree species and age classes across the landscape (Knutson and Klaas 1998; Twedt and Wilson 2007).

Site-level Recommendations

- Any management activity in this community must attempt to avoid the introduction and spread of invasive species, particularly reed canary grass, to the understory (WDNR 2008a).

- Retain large live trees, cavity trees, snags, and coarse woody debris (Twedt and Wilson 2007).

- A variable retention silvicultural approach (Mitchell and Beese 2002) and “wildlife forestry” treatments such as clustered thinning and small (~1-3.5 acres) patch cuts (Twedt and Somershoe 2009; Norris et al. 2009) can be used to create and maintain structural complexity (canopy gaps, understory and sub-canopy layers) and mimic natural disturbance while allowing for regeneration; its effects on forest and bird communities should be monitored.

- Monitor levels of white-tailed deer herbivory and lower deer numbers where feasible (WDNR 2008a).

Ecological Opportunities

Ecological Landscape Opportunity Management Recommendations Central Sand Plains Major All Southeast Glacial Plains Major All Western Coulee and Ridges Major All Central Lake Michigan Coastal Important All Central Sand Hills Important All Forest Transition Important All North Central Forest Important All Northern Lake Michigan Coastal Important All Superior Coastal Plain Important All Western Prairie Important All Northeast Sands Present 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12 Northern Highland Present 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12 Northwest Sands Present 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12 Southern Lake Michigan Coastal Present 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12 Southwest Savanna Present 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12

Research Needs

- Assess the detailed landscape and site recommendations for bottomland hardwood forests in the southern U.S. developed by the Lower Mississippi Valley Joint Venture (LMVJV Forest Resource Conservation Working Group 2007) for applicability to the Midwest and develop similar recommendations for bottomland hardwood forests in Wisconsin.

- Develop large-scale planning approaches for floodplain systems that integrate ecological and conservation objectives with recreation and commodity production objectives (WDNR 2008a).

- Investigate the effects of breeding habitat quality at multiple scales on demographics of focal bird species.

- Investigate the short- and long-term effects of different silvicultural treatments on breeding birds in bottomland hardwood forests (e.g., by conducting pre- and post-harvest bird surveys).

- Develop silvicultural systems that can sustainably manage and regenerate bottomland hardwoods despite the presence of invasive species (particularly reed canary grass) and high levels of deer herbivory (WDNR 2008a).

- Continue research to identify effective biocontrols for invasive species (WDNR 2008a).

- Evaluate the historical, current and potential future status of floodplain oak savanna and cottonwood-willow forest, as well as their bird communities, significance to bird conservation, and management issues.

- Evaluate the future of bottomland hardwoods in Wisconsin, considering factors such as climate change, invasives, tree diseases, forestry and other human uses, watershed land use, and dam operation; with emphasis on forest establishment and succession; identify knowledge gaps.

Implementation

Key Sites

- Lower Baraboo River (Columbia Co.)

- Lower Chippewa River (Buffalo, Dunn, Pepin Cos.)

- Lower Kickapoo River (Crawford Co.)

- Lower Peshtigo River (Marinette Co.)

- Lower Sugar River (Rock Co.)

- Lower Wisconsin River (Columbia, Crawford, Dane, Grant, Iowa, Richland, Sauk Cos.)

- Lower Wolf (Outagamie, Shawano, Waupaca, Winnebago Cos.)

- Rush Creek (Crawford, Vernon Cos)

- St. Croix River (Pierce, Polk, St. Croix Cos.)

- Upper Mississippi River/Trempealeau National Fish & Wildlife Refuges (Buffalo, Crawford, Grant, La Crosse, Pepin, Pierce, Trempealeau, Vernon Cos.)

- Van Loon Bottoms (La Crosse, Trempealeau Cos.)

- Wyalusing to Dewey (Grant Co.)

Key Partners

- Driftless Area Initiative: http://www.driftlessareainitiative.org/

- Invasive Plants Association of Wisconsin: http://www.ipaw.org

- Lower Wisconsin State Riverway Board: http://lwr.state.wi.us/

- National Park Service: http://www.nps.gov/

- Natural Resources Conservation Service: http://www.nrcs.usda/gov/

- River Alliance: http://riveralliance.info/

- Standing Cedars Community Land Conservancy: http://www.standingcedars.org/

- U.S. Army Corp of Engineers: http://www.usace.army.mil/Pages/default.aspx

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: http://www.fws.gov/

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources: http://dnr.wi.gov/

- Wisconsin Wetlands Association:

- Wisconsin Woodland Owners Association: http://www.wisconsinwoodlands.org/

Funding Sources

- Knowles-Nelson Stewardship Fund: http://www.dnr.state.wi.us/org/caer/cfa/lr/stewardship/stewardship.html

- National Fish and Wildlife Foundation Upper Mississippi River Watershed Fund: http://www.nfwf.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Charter_Programs_List&

- CONTENTID=15402&TEMPLATE=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm

- NRCS: Wetlands Reserve Program: http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/programs/wrp/

- Wisconsin Managed Forest Law: http://dnr.wi.gov/forestry/ftax/

Information Sources

- Hamel, P.B. 2006. Adaptive forest management to improve habitats for Cerulean Warbler. Proceedings of Society of American Foresters National Convention 2006. Available online at: http://www.srs.fs.udsa.gov/pubs/ja/ja_hamel009.pdf

- Lower Mississippi Valley Joint Venture (especially Bookshelf and Research pages): http://www.lmvjv.org/

- Steele, Y. (editor). 2007. Important Bird Areas of Wisconsin: Critical Sites for the Conservation and Management of Wisconsin’s Birds. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources PUB-WM-475-2007, Madison, WI.

- U.S. Forest Service North Central Region Bottomland Hardwoods Web-based Forest Management Guide: http://nrs.fs.fed.us/fmg/nfmg/bl_hardwood/index.html

- Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center, Migratory Birds: http://www.umesc.usgs.gov/terrestrial/migratory_birds.html

- Upper Mississippi River Forest Partnership: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/watershed/upper_mississippi_partnership/

- WDNR Silviculture and Forest Aesthetics Handbook: http://dnr.wi.gov/forestry/Publications/Handbooks/24315/

- WDNR Old-growth and Old Forests Handbook, Bottomland Hardwood Chapter: http://intranet.dnr.state.wi.us/int/mb/handbooks/24805/24805.pdf

- Wilson, D.C. (editor). 2008. Managing From a Landscape Perspective: A Guide for Integrating Forest Interior Bird Habitat Considerations and Forest Management Planning in the Driftless Area of the Upper Mississippi River Basin, Version 1.1: http://www.driftlessareainitiative.org/pdf/Managing_from_a_

- Landscape_Perspective_Web_Version_1_1.pdf

References

- Cowardin, L. M., V. Carter, F. C. Golet, E. T. LaRoe. 1979. Classification of

wetlands and deepwater habitats of the United States. U. S. Department of

the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. Jamestown, ND: Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Home Page.

http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/1998/classwet/classwet.htm (Version 04DEC98). - Curtis, J.T. The Vegetation of Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI.

- Easterling, D.R., G.A. Meehl, C. Parmesan, S.A. Changnon, T.R. Karl, and L.O. Mearns. 2000. Climate extremes: observations, modeling, and impacts. Science 289(5487): 2068-2074.

- Hale, B.W., E.M. Alsum, and M.S. Adams. 2008. Changes in the floodplain forest vegetation of the Lower Wisconsin River over the last fifty years. American Midland Naturalist 160: 454-476.

- Hansen, J. 2006. Yellow-throated Warbler. Pages 524-525 in N.J. Cutright, B.R. Harriman, and R.W. Howe (eds.). Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Wisconsin. Wisconsin Society for Ornithology, Inc., Waukesha, WI.

- Jentsch, A., J. Kreyling, and C. Beirerkuhnlein. 2007. A new generation of climate-change experiments: events, not trends. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 5(7): 365-374.

- Knutson, M.G. and E.E. Klaas. 1998. Floodplain forest loss and changes in forest community composition and structure in the Upper Mississippi River: a wildlife habitat at risk. Natural Areas Journal 18(2): 138-150.

- Knutson, M.G., J.P. Hoover, and E.E. Klaas. 1996. The importance of floodplain forests in the conservation and management of neotropical migratory birds in the Midwest. Pages 18-188 in F.R. Thompson (ed.). Management of Midwestern Landscapes for the Conservation of Neotropical Migratory Birds. General Technical Report NC-187. USDA Forest Service, North Central Forest Experiment Station, St. Paul, MN.

- Knutson, M.G., G. Butcher, J. Fitzgerald, and J. Shieldcastle. 2001. Partners in Flight Bird Conservation Plan for the Upper Great Lakes Plain (Physiographic Area 16). USGS Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center in cooperation with Partners in Flight, La Crosse, WI.

- Kotar, J. and T.L. Burger. 1996. A Guide to Forest Communities and Habitat Types of Central and Southern Wisconsin. Department of Forest Ecology and Management, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI.

- LMVJV Forest Resource Conservation Working Group. 2007. Restoration, Management, and Monitoring of Forest Resources in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley: Recommendations for Enhancing Wildlife Habitat. Edited by R. Wilson, K. Ribbeck, S. King, and D. Twedt. Lower Mississippi Valley Joint Venture, Vicksburg, MS

- Miller, J.R., M.D. Dixon, and M.G. Turner. 2004. Response of avian communities in large-river floodplains to environmental variation at multiple scales. Ecological Applications 14(5): 1394-1410.

- Mitchell, S.J. and W.J. Beese. 2002. The retention system: reconciling variable retention with the principles of silvicultural systems. The Forestry Chronicle 78(3): 397-403.

- Mossman, M.J. 1988. Birds of southern Wisconsin floodplain forests. Passenger Pigeon 50(4): 321-337.

- Mossman, M.J. and P.E. Matthiae. 1988. Wisconsin’s bird habitats: introducing a new series. Passenger Pigeon 50(1): 43-51.

- Norris, J.L., M.J. Chamberlain, and D.J. Twedt. 2009. Effects of wildlife forestry on abundance of breeding birds in bottomland hardwood forests of Louisiana. Journal of Wildlife Management 73(8): 1368-1379.

- Sample, D.W. and M.J. Mossman. 1987. Managing Habitat for Grassland Birds: A Guide for Wisconsin. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources PUBL-SS-925-97, Madison, WI.

- Shaw, Samuel and C. Gordon Fredine. 1971. Wetlands of the United States. Circular 39. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C.

- Twedt, D.J.and S.G. Somershoe. 2009. Bird response to prescribed silvicultural treatments in bottomland hardwood forests. Journal of Wildlife Management 73(7): 1140-1150.

- Twedt, D.J. and R.R. Wilson. 2007. Management of bottomland hardwood forests for birds. Pages 49-64 in T.F. Shupe (editor). Proceedings of the 2007 Louisiana Natural Resources Symposium. Louisiana State University AgCenter, Baton Rouge, LA.

- UMRGLJV. 2007. Upper Mississippi River and Great Lakes Region Joint Venture Implementation Plan (compiled by G. J. Soulliere and B. A. Potter). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fort Snelling, Minnesota, USA. Online at: http://www.uppermissgreatlakesjv.org/docs/JV2007All-BirdPlanFinal2-11-08.pdf

- USDA Forest Service. 7 August, 2008. North Central Region Bottomland Hardwoods Web-based Forest Management Guide. USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station. Accessed 07 April, 2011. http://nrs.fs.fed.us/fmg/nfmg/bl_hardwood/index.html

- WDNR. 1992. Wisconsin Wetlands Inventory Classification Guide. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, PUBL-WZ-WZ023.

- WDNR. 2005. Wisconsin Wildlife Action Plan. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI.

- WDNR. 13 October, 2008a. Natural Communities of Wisconsin: Floodplain Forest. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI. Accessed 26 January, 2011. http://dnr.wi.gov/org/land/er/communities/index.asp?mode=detail&Code=CPFOR024WI

- WDNR. 2008b. Old-growth and Old Forests Handbook, Bottomland Hardwood Chapter. State of Wisconsin, Department of Natural Resources, Handbook 2480.5, Chapter 18. 24 pp.

- WDNR. 2010. Silviculture and Forest Aesthetics Handbook. State of Wisconsin, Department of Natural Resources, Handbook 2431.5, Madison, WI.

- WDNR. 2011. Ecological Landscapes of Wisconsin Handbook, Assessment of Current Conditions, Southern Forest Communities Chapter. DRAFT. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Handbook 1805.1, Chapter 2. 34 pp.

- WICCI. 2011. Wisconsin’s Changing Climate: Impacts and Adaptation. Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts. Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI.

Contact Information

- Author: Yoyi Steele, Yoyi.Steele@Wisconsin.gov. Posted June 2011.

Steele, Y. 2011. Bottomland Hardwood Habitat Page. In Paulios, A. and K. Kreitinger (eds.). 2007-2012. The Wisconsin All-Bird Conservation Plan, Version 1.0. Wisconsin Bird Conservation Initiative. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI.